Former Nonviolence Institute Streetworker Says Organization’s Close Ties to Police Problematic

GoLocalProv News Team and Kate Nagle, News Editor

Former Nonviolence Institute Streetworker Says Organization’s Close Ties to Police Problematic

“I don’t think the public really knows what’s going on,” said Angelo Adams, who worked with the organization for several years more than a decade ago.

He then severed ties with the Institute after witnessing a murder of a young man on the street. Adams has continued to monitor the organization and its changes over the years.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTFirst founded in 2000, when 30 people were murdered in Providence, and 45 were killed statewide, the Nonviolence Institute recently hosted a forum in May with elected officials and community leaders after two homicides took place in less than 48 hours -- as well as the worst shooting in the city’s history.

“I want the Nonviolence Institute to exist. It was something hugely important to me as someone who has worked in Providence my whole life,” Adams said. “But I think it needs to be a safe haven. But information is getting shared with police, [who are then] raiding houses. It looks good in public, but nine times out of ten, these guys are then scared and manipulated. Now they’re an informant and a snitch and they know what will happen next. This is what I'm seeing."

“How can we resolve issues between a group of people without involving the police? Right now, they can’t talk to anyone. I’m on the street, I know if a kid needs a job, needs a GED, needs Job Corps, needs a place to stay — or needs to get out of town," he said. "There should be somewhere where we can have someone in the middle and mediate the situation.”

Last weekend, Providence Police made arrests and confiscated weapons from individuals who had recently been the victims of gun violence.

“I can tell you from tons of experience, no one wants to carry a gun around,” Adams said.

“It becomes, ‘I have to have it to protect myself or else I'll have to kill someone,'" he added. "And that’s a terrible Catch-22."

Current Executive Director Cedric Huntley did not respond to request for comment on Tuesday.

From Foster Homes to Military to Working With City Youth

Adams, now 52, said he grew up with a largely absentee mother, and as one of seven siblings with different fathers, lived with various family members across the city, as well as foster homes.

“I was dropped off at my aunt’s when I was around 7 and didn’t see my mom for years after that,” he said. “We would have to read the Bible every night. That’s how I learned to read.”

Adams said he vividly remembers certain incidents from his youth, including being called a “chocolate bar” by a white classmate at Asa Messer Elementary.

“I remember ‘Officer Friendly’ coming to school. I really wanted to be a police officer. Of course, I couldn’t tell that to anybody,” he said.

After graduating from Hope High School, Adams entered the Marines, and then, he said, came back to try and take care of his siblings.

“I was convicted in 1993 of delivering cocaine. That was the hustle for my brothers,” he said. “I was a first-time offender and I knew I was a small fish [in the sting operation]. They processed me, asked me about the supplier, I thought I was getting out. Then I was taken to the ACI.”

“Walking through the doors, I went from being scared to brokenhearted. I saw a bunch of people I knew. It looked like when I took my son to the dog pound — except it was people in cages, wasting time,” he said. “It didn’t matter, I had to do a minimum of ten days.”

Adam said working after that with the Nonviolence Institute -- which was initially formed as the “Institute for the Study and Practice of Nonviolence” -- changed his life.

“It took me until I was 28 to know punching someone in the face isn’t answer. I just want the Nonviolence Institute to do what they’re supposed to be doing,” he said. “I was supposed to be a police officer and ended up in prison.”

It was a night in 2005 however that Adams said changed his life forever.

“The rumor was that a guy had gone and shot up someone else and they were looking for him — ‘JR’ — and people came out that night,” said Adams, of the shooting death of Fernando Ventura "Jr" on Chalkstone Avenue.

Adams said he was there when it happened, and that he was detained by police immediately following and questioned at the station.

“I mean, why didn’t they shoot me? Was it because they knew me?” said Adams of Ventura's assailants. Adams says he still suffers from PTSD from the incident.

Following the shooting, Adams says he told the Nonviolence Institute he needed to take a few weeks off; he said their side of the story at the time was he resigned.

“If no one intervenes, it becomes about survival, and people want revenge,” said Adams, noting that a number of people who knew who went to prison in the early 2000s are now coming back out after serving time. “And we haven’t resolved the conflicts. At the end of the day people just want an identity and a job.”

“We need the Nonviolence Institute to prevent what’s happening,” said Adams. “They need people they can trust — this is life and death.”

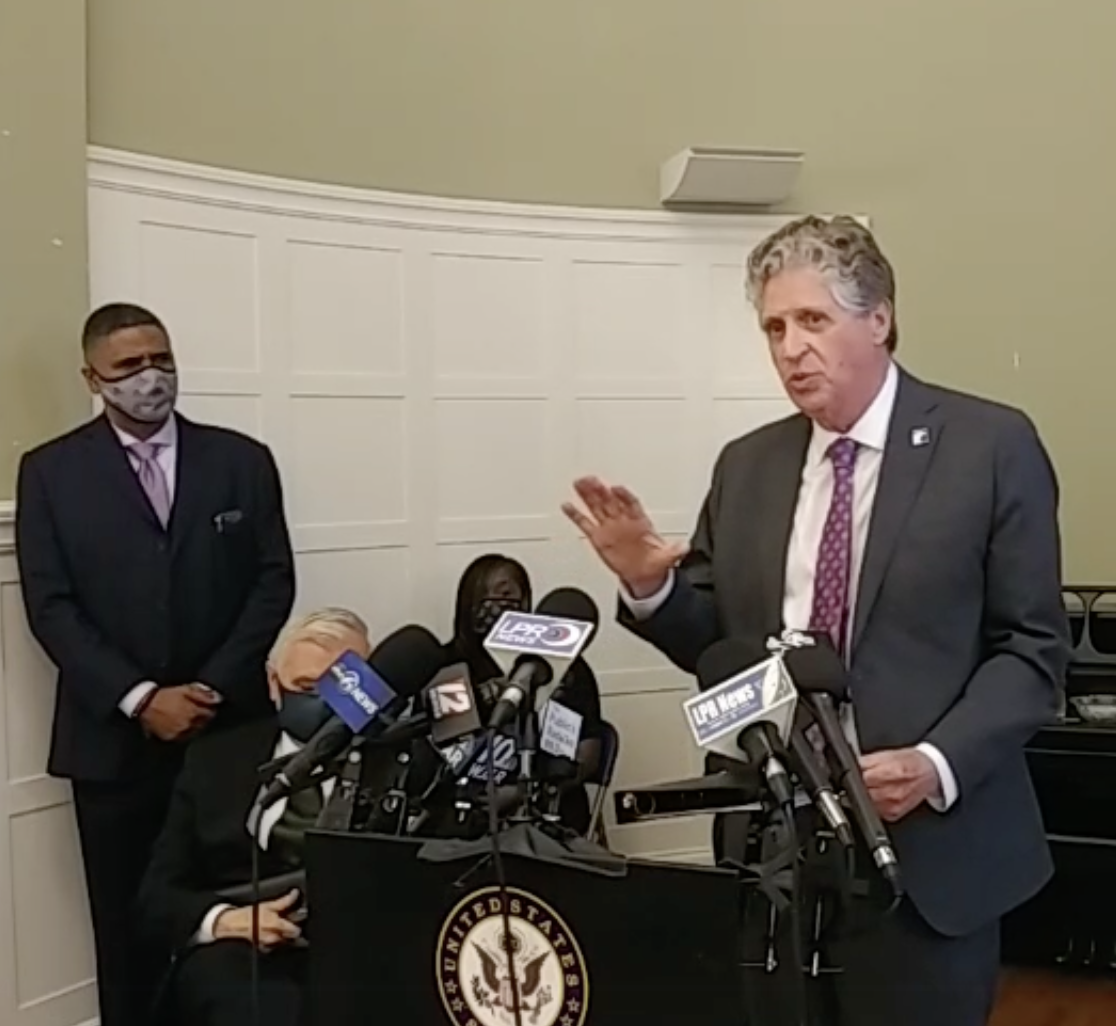

Providence Police Chief on Relationship

“It’s a unique relationship. There are cities across the country where police try and engage and interact in partnership with an entity [like the Institute],” Clements.

“We’ve worked at this over the years. It might not be perfect, but we still have the same mission, which is to address young men who have disputes that lead to gun violence,” he said. “I can say there isn’t a lot of information shared [between the Institute and police], but on parallel fronts, we confront the issues in general. There are things they can’t do alone, and things we can’t do alone, if we have a back and forth problem.”

“I know the teamwork has been helpful,” said Clements. “We can empirically say we’ve knocked back retaliation shootings. If you have two combatants in a hot dispute, we handle the initial end of it, whether that’s shots fired, a shooting, or a homicide. On the back end is the Institute, which is not a role we perform. The relationship is obviously necessary and essential."

“We built the system here, that’s why they took [Institute founder] Teny [Gross] to Chicago," said Clements, of Gross being recruited to work in Illinois. "I know it’s not perfect."

Adams, however, thinks the relationship with police should end.

The Institute’s latest 990 filing for 2018 states its mission is to “teach, by word and example, the principles and practices of nonviolence, and to foster a community that addresses potentially violent situations with nonviolent solutions.”

Total revenue for 2018 was nearly $1.9 million; salaries amounted to nearly $1.5 million. Then-Executive Director PJ Fox was listed as making just over $75,000.

"I hope new leadership severs ties [with police]," Adams said.