PART TWO INVESTIGATION: Legal Loophole Saves Brown Millions in Taxes

Stephen Beale, GoLocalProv News Contributor

PART TWO INVESTIGATION: Legal Loophole Saves Brown Millions in Taxes

If the state law on tax exemptions for nonprofits was strictly applied, Brown would owe as much as $4.6 million in property taxes—if not more. The law restricts the exemption to properties used exclusively for educational purposes, but Brown claims the exemption for its rental properties and commercial properties as well. The law also caps the exemption to one acre, but Brown claims it for more than 21 properties that exceed an acre. (Read yesterday’s GoLocalProv report.)

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTBrown says its charter trumps state law

That charter indeed can override the limitations imposed by the state law, according to legal experts interviewed by GoLocalProv.

However, that exemption is not unlimited, according to Bob Craven, a former state assistant attorney general. “Any defense to paying property taxes by Brown University saying their colonial charter allows Brown to be tax exempt … would be subject to an interpretation of original intent,” Craven told GoLocalProv. He said such an analysis of the original intent, by a court, would examine how the intent of the charter relates to the properties Brown has and what their purpose is.

“If they were in the casino business would they be tax exempt?” Craven added. “The answer is clearly ‘no.’”

He said some of the properties identified in the GoLocalProv analysis might fall outside the original intent of the charter.

He pointed to the Brown Faculty Club—in which membership is open to members of the public who are “friends” of the university—as one example of how Brown is not paying its fair share of taxes. “I don’t think there’s any question there should be some allocation of the property taxes based on its membership,” Craven said.

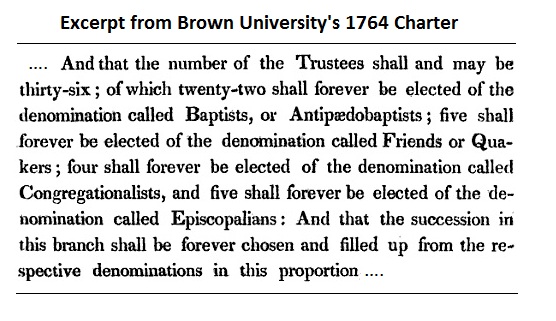

Charter also restricts religious denomination of trustees, president

The original colonial charter was granted in 1764 by the colonial Governor and General Assembly before there was a United States of America and a State of Rhode Island. It appeals to the authority of its own royal charter as a basis for issuing a charter to Brown.

The same document mandates that a certain number of Baptists, Quakers, Congregationalists and Episcopalians must serve on the board of trustees and says the president can be fired for changing religious denominations. It also requires that all trustees take a pledge of allegiance to the then-sovereign King George III and his successors—all provisions that are obviously not in effect today.

When asked how relevant that charter is now, Quinn pointed to a revised charter that Brown published in 1945. That document no longer had many of the now-outdated provisions of the original charter, such as the rules on how religious denominations, but it kept the blanket exemption on taxes from the 1764 charter virtually unchanged.

Supreme Court battle

Such tax exemptions were hardly unusual in the 1700s and are rooted in English common law, according to retired Brown University historian Gordon Wood. He said the exemptions were issued to institutions that were perceived as providing a public good, such as colleges and hospitals.

But can exemptions granted by a charter that was issued before the United States even existed be revoked?

The court ruled that Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution barred the state from making any changes to Dartmouth’s colonial charter. That section, in part, states that no state shall make any “Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.” The court concluded that Dartmouth’s colonial charter was equivalent to a contract.

The same logic applies to Brown’s charter in Rhode Island, Conley said. The only way that the charter itself can be changed, he said, is if Brown consents to it.

Nonprofit exemptions under fire

It would be tough for the City of Providence, or anyone else, to mount a legal challenge to Brown’s tax exemption, according to Gary Pannone, an attorney and managing partner at Pannone Lopes Devereaux and West. “A grant by the General Assembly is a significant right that they have that, if challenged, the burden is going to be on whoever’s challenging it,” Pannone said.

The city has tried once in the past to challenge a nonprofit’s tax exemption. In 1995, Providence sent Rhode Island Hospital a tax bill for an office building which it rented out to doctors and other tenants. The hospital sued the city in a case that ultimately wound up at the state Supreme Court, which decided against the city. In its ruling, the court cited a similar case involving Woonsocket Hospital in 1974.

The town’s move did not land it in court. Instead, the institute sent the town a check, DeAngelis said.

But the town’s success turned out to short-lived. Last month, a Chinese holding company purchased the land and buildings and plans to turn them the property into a boarding school, which would be tax-exempt, according to DeAngelis.

Debate over Brown

In its defense, Brown’s boosters are quick to point out the contributions it contributes to Providence. Those contributions range from tangible benefits like construction jobs and tourist dollars to the harder-to-measure contributions Brown makes to the city’s cultural life.

But that is not relevant to the issue of whether it owes taxes on some properties, Craven said. “I think GTECH is providing a lot of jobs,” Craven said. “Bank of America provides jobs, but they’re paying taxes.”

If you valued this article, please LIKE GoLocalProv.com on Facebook by clicking HERE.