Scoundrels: Chapter 3 Part 1, Cash in the Dumpster

Paul Caranci & Thomas Blacke, Authors

Scoundrels: Chapter 3 Part 1, Cash in the Dumpster

The book uses several infamous instances of political corruption in Rhode Island to try and define what has not been easily recognized, and has eluded traditional definition.

The book looks at and categorizes various forms of corruption, including both active and passive practices, which have negative and deteriorating effects on the society as a whole.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTBuy the book by CLICKING HERE

Chapter 3

Cash in the Dumpster

Providence Journal investigative reporters and staff writers Tracy Breton, Mike Stanton, David Herzog, and W. Zachary Malinowski spent hundreds of hours scouring through tens of thousands of pages based heavily upon court documents and records related to the DiPrete case. Collectively, they provided in-depth coverage of the case in real time. This chapter is based heavily upon their research and the work they produced and published in a series written for The Providence Journal by them.

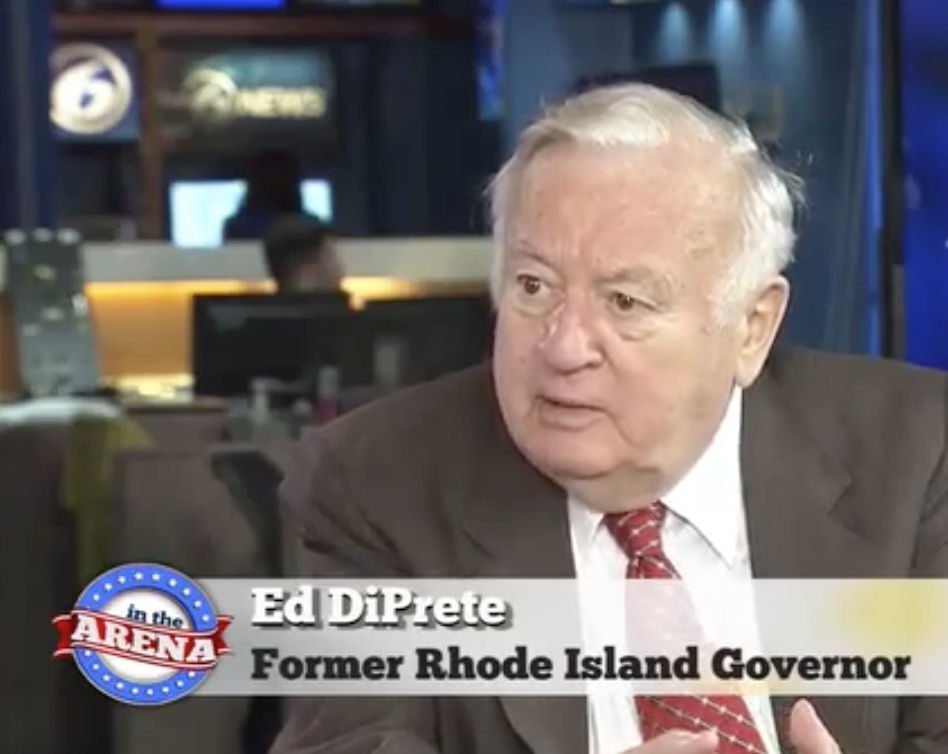

There are occasions when an unscrupulous activity in the private sector can spill over into the public sector creating an environment rife for political scandal, a sort of “perfect storm” for corruption. Perhaps this is one way to recount the saga of Governor Edward DiPrete.

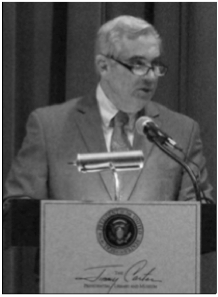

Edward DiPrete, just three years after leaving office, became the first Governor of Rhode Island to be charged with corruption. The investigation started four years before that, in 1990, and resulted from the discovery of a $13 million bank embezzlement scheme orchestrated by Joseph Mollicone, the bank’s President. The crime would later be described as the event responsible for setting off “Rhode Island’s worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.”

The story of this scandal involves many different players and events each intimately intertwined with the DiPrete story. Like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, each fragment contributes to the ultimate disposition of the scandal. Recounting each element of this tale sequentially will help bring into focus the eventual charges against Governor Edward DiPrete.

Joe Mollicone – Providence Banker and Entrepreneur –And His Partner Rodney Brusini

Thirty-four-year-old lawyer J. Richard Ratcliffe was one of Attorney General James E. O’Neil’s first appointments to the newly created 5-member Special Prosecutions unit of the Attorney General’s office. With a focus on white-collar crime, formation of the unit was long overdue and was already overburdened with potential cases when Ratcliffe accepted the appointment. He was investigating a case involving the Pastor of St. Anthony’s Church in North Providence who was accused of embezzling some $200,000 from the collection plate and bingo money from the parish family when the call came from O’Neil regarding the alleged embezzlement of $13 million from Heritage Loan & Investment Co. by its President, Joseph Mollicone. Later that day, after confronting Mollicone, O’Neil “ordered a grand jury investigation. A week later, on November 8, 1990, Joseph Mollicone vanished,” just two days after DiPrete lost his bid for a fourth, two-year term as Governor.

Less than two weeks following Mollicone’s disappearance, the lame duck Governor closed Heritage Loan & Investment Co., but it was too late. Mollicone’s actions and the bank’s collapse “drained its insurer, the private Rhode Island Share and Deposit Indemnity Corp. (RISDIC). And, the draining of RISDIC imperiled the savings of several hundred thousand depositors at a total of 45 Rhode Island banks and credit unions.” Despite pleas from Attorney General O’Neil that it was a conflict of interest due to the potential involvement of top DiPrete aids, DiPrete ordered an investigation by the state police. In Rhode Island, such an investigation falls under the jurisdiction of the Governor’s office.

Just as the RISDIC revelations were uncovering how a corrupt political system and a corrupt banking system can nourish each other, those with insider knowledge quietly began to systematically withdraw their money from the affected institutions. “On December 30, 1990, two days before Governor DiPrete left office, the directors of the now-drained Rhode Island Share and Deposit Indemnity Corp. voted themselves out of business. RISDIC’s president … went straight from the meeting to pull his money out of a RISDIC-insured bank before the vaults slammed shut.” This is an opportunity that ordinary Rhode Islanders could not take advantage of since the RISDIC proceedings were kept quiet. As a result, many bank board members, some of whom were politically connected as well, were charged with crimes in separate investigations of the RISDIC scandal. Two days later, on the day of Governor Bruce Sundlun’s inauguration, the RISDIC banks were closed per order of the new Governor, separating “hundreds of thousands of people from their savings.”

At just about the same time, an employee of the state Department of Employment Security phoned the Attorney General’s office complaining that some of the Governor’s “people” were pressuring him to enter into a lease for the Jesse Metcalf Building in downtown Providence, a building that had been purchased and rehabilitated in 1988 by Joseph Mollicone and his partner Rodney M. Brusini. Brusini was a long-time friend of DiPrete and once acted as his chief fundraiser. Mollicone owned several buildings, many of which were leased by departments of state government. However, for greedy insiders, it apparently wasn’t enough that Employment Security had already moved into the Metcalf Building in 1990, Mollicone now wanted the state to rent the 5th floor as well, space, according to Providence Journal investigative reporters, the state didn’t even need.

Paul Valliere, the Director of Finance for the Department of Employment Security, told the Attorney General that it was his boss, John S. Renza, an associate from the days when DiPrete served as Mayor of Cranston, that introduced him to Mollicone and Brusini at a meeting intended to provide inside information regarding the Department’s rental needs to the Metcalf Building owners.

Not only did the state wind up renting the 5th floor space for more money than the landlords were originally asking for, but the owners then presented a $350,000 bill for renovations to the space that the state never authorized. The state paid the bill anyway over the objections of Valliere who was told that he was not a “team player.”

“Despite resistance from Valliere and others, the state’s rental of the top floor moved forward but eventually fell through when Paul Valliere went to the Attorney General after Mollicone’s disappearance.” Although citizens protested the bank closings and besieged the Attorney General’s office with hundreds of tips on suspicious loans and unscrupulous politicians, the Mollicone lease arrangements remained the prime focus of investigators.

Ratcliffe assembled a team of investigators that included paralegal Peter Blessing who had real estate expertise and Lt. Robert P. Mattos, a State Police Detective with a reputation for latching onto the jugular of those he suspected of wrong doing. Sometime in January of 1991, Blessing came across a check in Mollicone’s bank records made out to Anjoorian Carpets in the amount of $875.00. In the memo box were the words “Renza’s rug.” This was of particular interest because a few days earlier, under Grand Jury questioning by Ratcliffe, Renza couldn’t recall the details of the lease, “and denied having spoken to Mollicone or Rodney Brusini before the agency put its rental requirements out to bid.”

The new information prompted a second trip by Renza before the Grand Jury. This time, under intense questioning about the rug, Renza collapsed and was taken to Kent County Memorial Hospital where, despite his condition, Lt. Mattos was able to obtain Renza’s permission to search his home. Once recovered, Renza was arrested and charged with perjury, bid rigging and obtaining money under false pretenses. Facing an onslaught of legal problems, Renza suddenly remembered everything. “Renza admitted that he had discussed the Metcalf Building lease with co-owners Joseph Mollicone and Rodney Brusini before the state advertised its need for office space. Brusini was pushy, Renza recalled; both he and Mollicone had smugly predicted that their bid would be the lowest.

Mathias J. Santos – Top Aide In DiPrete’s Department Of Administration, Does DiPrete’s Bidding In The Assignment Of A & E Contracts

Renza also told investigators that after his state agency had moved into the Metcalf Building, he was pressured to rent more space, on the top floor. When he protested that the space was unnecessary, Renza said he received a phone call from an angry DiPrete aide. “‘God Damn it,’ Renza recalled the man’s shouting, ‘I’m telling you to sign it!’ ” Renza identified the caller as Mathies Santos, a loyal member of the DiPrete Administration and friend of Brusini and Dennis L. DiPrete, the Governor’s son. And this wasn’t the only time that Santos, who served on the State Properties Committee, a powerful committee that approved state leases and purchases, pressured someone to sign state leases. “Henry S. Woodbridge, Jr., the director of another job-training agency, told investigators that Santos had screamed at him to move his agency into the building. When Woodridge refused, he told investigators, he received a phone call from Henry Fazzano, DiPrete’s chief of staff and another Metcalf Building co-owner. Fazzano ordered Woodbridge to move into the building, but Woodbridge still refused. Fazzano later denied doing anything improper.”

Renza wasn’t alone with his allegations of political interference. The State Fire Marshall, Everett Ignagni, also revealed details of a phone call he got from a union official telling him how irate Jake Kaplan, a DiPrete contributor, and Dennis DiPrete were that he was resisting attempts to have him rent space in Jake Kaplan’s South Providence building. It was also discovered that Santos helped arrange the state’s leasing of office space that was paid for even though the state didn’t use it. Additionally, Santos was instrumental in obtaining for the owners thousands of dollars in renovations not previously approved by the state. All this after Santos received a $142,500 loan from Heritage Investment & Loan Co. after a bad credit history resulted in a loan rejection by Fleet Bank. Despite these findings, and contrary to the judge’s assertions, “the DiPrete-case investigators believed that Santos had been involved in “this overall scheme,” as a prosecutor would later refer to the state’s rental of Joseph Mollicone’s building. But they regarded Santos as merely a messenger – someone who did the DiPrete’s’ bidding.” Even though a judge would later “rule that the state had knowledge of possible criminal activity involving Santos, ranging from conflict-of-interest violations to possible bribery and/or extortion,” prosecutors argued that the behavior was “certainly bad, but not criminal.” It appeared that prosecutors were more interested in having Santos as a witness than a suspect. Under an immunity agreement, Santos told investigators that he took his direction regarding leases from Brusini. He also said that both Brusini and Fazzano told him they wanted out of their partnership on the Metcalf Building but could only do so if the building were fully occupied. Santos, in defending his actions also said that the construction bills for which the building partners were reimbursed by the state were legitimate.

The big news, however, came in March of 1991. That’s when Santos revealed to investigators that he had also been involved in choosing architects and engineers for state construction projects as well. “Santos said that Dennis DiPrete, the governor’s engineer son, would tell Santos whom to hire for projects. Although Dennis DiPrete held no government position, said Santos, Santos followed his instructions because he assumed that the son was communicating his father’s wishes.”

Frank N. Zaino, Engineer and Political Supporter of Governor DiPrete, Provides Structure to the ‘Contracts For Sale’ Scheme

With these revelations, and after hearing rumors of state contracts for sale, the investigation turned in a new direction. Investigators found a letter written in 1988 by architect Walter Powers to Dennis DiPrete in which Powers asks Dennis if he could “possibly motivate some positive activity by the state.” For the first time, investigators had proof of the Governor’s son’s involvement. Meanwhile, Lt. Mattos was receiving word from other architects that several other engineers and architects had paid Dennis DiPrete for state contracts. “The tipsters identified Frank Zaino as a key player.” Other architects he worked with included David Presbrey, Donald R. Conlon, and Norton Salk. Although Conlon and Salk testified before the Grand Jury that they had done nothing wrong, Mattos believed he had evidence that Salk was a straw donor to DiPrete as he had his assistant make the donation after Salk had reached his legal contribution limit. (A straw donor is defined as one who makes a contribution on behalf of another person who has already contributed the maximum amount allowed by law. It is illegal in Rhode Island to make a “straw donation”.) Further, Salk instructed the assistant to lie about where the money came from. Additionally, investigators found two of Salk’s checks made out to Zaino. Salk was offered immunity for his truthful testimony and jumped at the opportunity. “Salk now told the Grand Jury that in 1990 he had asked Frank Zaino – whom he’d known for 30 years – to help him get bigger state jobs. Zaino told Salk to come up with $25,000. So, over a six-week period, Salk wrote three checks totaling the requested amount (Zaino later returned one of the checks telling Salk he had paid too much.) Salk didn’t get the jobs he wanted. He told the Grand Jury that Zaino had never explicitly promised him the jobs; he had only said come up with $25,000.”

The testimony was enough for the Grand Jury to indict Donald Conlon for perjury. Investigators also discovered that money from Conlon’s firm was transferred to Zaino’s firm, and that Conlon had also given money to friends to donate to the DiPrete campaign once he had reached the legal contribution limit.

Conlon decided to tell the Grand Jury what he knew. According to his version, it started innocently enough. Conlon simply donated to the campaign of a sitting governor. But once he reached the legal limit, “he followed Zaino’s instructions and gave money to friends to contribute to the campaign in their names. He also started giving cash to Zaino (something also prohibited under campaign finance law) – generally $4,000 to $5,000 a year. As the demands for money grew, Conlon told the Grand Jury, he opened a line of credit on his house. In 1988, after winning a $430,000 contract to work on the State Training School, Conlon tried to cash a check for $10,000. The teller told him that federal law required her to report any transactions of $10,000 or more. Rather than face that scrutiny, he settled for $9,950, which he said he gave to Zaino. Zaino told Conlon that he would deliver the cash to Dennis DiPrete, the governor’s son. Zaino spoke often of the younger DiPrete as his contact for state jobs, Conlon testified. After Conlon got the Training School contract, Zaino passed along a request from Dennis DiPrete: Conlon should hire Dennis’s college roommate as an engineering subcontractor on the job. Conlon did.”

Presbrey was the next to testify before the Grand Jury on March 6, 1992. Under a grant of immunity, “he testified that he believed the contributions had been necessary to get state work. And as he gave more money, the jobs rolled in: the new Washington County Court House, the new Block Island airport terminal, the expansion of the Davies Vocational Technical school…The contributions began with checks for tickets to DiPrete fundraising events, which Presbrey would deliver to Rodney Brusini at the F.A. DiPrete Insurance Agency, in Cranston. Brusini was the Governor’s chief fundraiser, although Brusini held no government post, Presbrey testified. Presbrey made sure to tell him which state projects he was interested in. Eventually, Presbrey started dealing instead with Frank Zaino. From their conversations, Presbrey gathered that Zaino was reporting to Dennis DiPrete, the Governor’s son. But Presbrey, like Salk and Conlon, testified that he never dealt directly with Dennis DiPrete concerning contributions for state contracts. “My sense,” Presbrey told a Grand Jury “was that Dennis DiPrete was making the decisions, or Dennis and the Governor were making the decisions, on who was going to be doing the A and E work” – the architect and engineering.”

Presbrey also testified that he too continued to make contributions to Governor DiPrete after he reached the legal $2,000 limit by making contributions of cash. “Between checks and cash, his annual contributions went from $2,000 to $4,500, to $6,150, to more than $27,500, in DiPrete’s last two years.”

DiPrete’s co-conspirators were running for cover. One friend of Frank Zaino told the Grand Jury that he would not go to jail to protect DiPrete.

Zaino And DiPrete: A Retrospective on Friendship

Zaino, a Charles Street native, eventually moved to Western Cranston where he met his neighbor, Edward DiPrete. “They became good friends, however, only after DiPrete was elected to serve on the Cranston School Committee. DiPrete was serving on its Building Committee when Zaino was doing work on the city’s schools.” Zaino’s career was burgeoning just as his business was growing and he was elected President of the Rhode Island Society of Professional Engineers. He “led the Society as it discussed the need to reform government-contracting rules, in the wake of scandals in Maryland involving Vice President Spiro Agnew. Ironically, Richard Nixon’s Vice President had been forced to resign after pleading no-contest to taking kickbacks for state contracts when he was Governor of Maryland.”

Zaino’s relationship with DiPrete blossomed and DiPrete’s Agency provided Zaino’s insurance needs while their wives became close church friends. DiPrete’s eventual political rise took him from School Committee to Mayor, and Zaino’s influence grew. “One Cranston architect recalled that Zaino was ‘in and out of the Mayor’s Office all the time.’ This architect said that he relied on Zaino, his friend, to tell him where he stood on city contracts. The architect said that, to get work, Zaino had advised him: “You’ll have to contribute heavily….Zaino would later tell a Grand Jury that payments made to DiPrete fundraiser Rodney Brusini were ‘tied to how much work you got…in other words, if you did a lot of work, you’d better put in a lot of money.”

In 1984, when DiPrete ran for Governor for the first time, Zaino was his primary fundraiser, not only raising significant revenue for the cause, but also donating in excess of $20,000 himself, most of it in cash that was given directly to Brusini according to his Grand Jury testimony. Once DiPrete was elected, but even before he was inaugurated, Zaino was planning his future inquiring of outgoing Governor J. Joseph Garrahy if he knew “of any big state contracts coming up for bid.”

While the former Governor wasn’t of much help, Zaino found his own project in the Frank Licht Judicial complex on Benefit Street in Providence. Zaino testified before the Grand Jury that he went to DiPrete friend, fundraiser and colleague, Rodney Brusini. “Brusini told Zaino," according to Grand Jury testimony, "that he would talk to Governor DiPrete about the courthouse contract." When time passed with no word, Zaino began to worry. Finally, he asked his wife, Rosemarie Zaino, to talk to Patricia DiPrete. The two had become close friends over the years. Subsequently, Zaino told the Grand Jury, he was able to get into the Governor’s State House office to express his anxiety about getting the courthouse project. DiPrete promised to have his Chief of Staff track it. Later, according to Grand Jury testimony, Zaino received a phone call from Brusini: The job was his – with a catch…. Brusini asked what was ‘customary’ for architects and engineers to pay to get state jobs. Zaino said he’d heard the going rate was 5 percent of the fee charged for a big project, 6 percent for a smaller project. Brusini, in his Grand Jury testimony, said he promised to take it up with the Governor, and later reported to Zaino that it was a deal.” Because the total project fee was $1 million, Zaino’s cost would be $50,000. After striking a deal to count the previous contribution of $20,000 he had made to DiPrete, he had to pay only $30,000. Zaino shared his 5-6 percent formula with other firms including Robinson Green Beretta Corp. who, after paying Brusini, was awarded the $30 million contract to build the state’s new medium-security prison. Brusini later testified that he “had steered state projects to DiPrete-campaign contributors even though he had held no official position in state government.” But Zaino’s fortunes soon started to fade.

The Governor’s Son Replaces Brusini As The “Ear To The Governor”

“It was sometime in 1988, Frank N. Zaino told the Grand Jury, that he began to sense a rift within the DiPrete camp. People were saying that Rodney Brusini, Ed DiPrete’s old friend, was on the outs. Zaino saw a new face emerging; the Governor’s 28-year old son.” Concerned that Brusini might be “skimming,” Governor DiPrete ordered Zaino to deal only with his son Dennis. The younger DiPrete later told Zaino that the payment from which they suspected Brusini of skimming was made by developer Richard Baccari on behalf of Leonard Garofalo in order for him to secure contract work for the prison intake center. Envelopes, thick with cash, flowed from Zaino to DiPrete in such large numbers that Zaino had to open a bank account in the names of his children to hide the money from his wife who had filed for divorce. “Meanwhile, Dennis DiPrete, who owned his own engineering firm, escalated his demands. In Grand Jury testimony, Zaino’s son recalled Zaino’s complaints: ‘That’s all they want – money, money, money.’ ” The demands would continue right up until DiPrete lost his 1990 campaign to two-time challenger, millionaire Bruce Sundlun. “Even then, Dennis DiPrete wouldn’t quit. In early 1991, with a new Governor in place, and most of Rhode Island embroiled in the banking crisis, he telephoned Zaino. Zaino later said that Dennis DiPrete ordered him to round up money that architects still owed for DiPrete-administration work they were doing.” When Zaino refused Dennis protested “they owe it to us.” But Zaino “said he would no longer shake people down.” DiPrete’s world was unraveling just as President George H.W. Bush was considering him for a federal appointment. State police began to pour through Zaino’s records and question his friends. Donald Conlon was indicted for perjury and Zaino believed he would talk. Zaino was offered a deal but refused when he learned he would have to plead guilty to extortion. Zaino got lucky, however, when Attorney General O’Neil agreed to an immunity deal for Zaino believing that he needed Zaino’s testimony to nail Dennis DiPrete.

By fall of 1991, Zaino had told investigators how he paid Dennis DiPrete in exchange for state contracts; how Dennis had told him that he kept a log of all contributors and their contributions and how everyone had to pay. Investigators learned how DiPrete replaced Brusini as the person to talk to if you wanted a contract. “One contractor told a Grand Jury that he had considered Dennis DiPrete an ear to the Governor’ ”

But more, the Governor watched out for Dennis. “In 1988, The Providence Journal carried stories chronicling complaints from Rhode Island environmental regulators. The regulators said they’d been pressured by the Governor’s office to approve wetlands permits for projects that Dennis DiPrete was working on. Officials at the Department of Environmental Management were also displeased at the state’s hiring of Domenic V. Tutela, an engineer and DiPrete loyalist, to conduct an environmental study, even though his firm had been rated last among the bidders.” By all accounts, it was the Governor, and not his son, that secured the work for Tutela. Michael M. Doyle, DiPrete’s former Chief of Staff who became one of the principals in the RDW Group, a high- powered Rhode Island-based public relations firm, testified that “the Governor loved Tutela.”

The Governor and his Son Are Connected to The RISDIC Scandal

By all reports Governor DiPrete and his son were close. They were also the subjects of the RISDIC investigation, which, in 1992, “revealed that Edward and Dennis DiPrete had been involved in two Cranston land deals financed by questionable loans. The Commission concluded that the loans had been based on faulty appraisals, and, in one instance, on property that was largely swampland. The Commission traced a money trail from failed Rhode Island credit unions into various DiPrete bank accounts. According to state records, Paul Marchionda, Dennis DiPrete’s partner from his engineering firm, and a partner in one of the ventures, testified that Dennis DiPrete had told him that the Governor was a silent partner.” Both DiPretes denied that the Governor was involved and said that the $30,000 check written to the Governor from Dennis was a reimbursement of Dennis’s college tuition money that the Governor had paid.

Perhaps no deal the DiPretes were involved in was as spectacular as the “Cranston Land Deal.” In this transaction, the DiPretes purchased land in 1988 and resold it on the same day for $2 million more than they paid, subject to a controversial zone variance that would allow for the construction of 240 apartments. Despite more than 100 residents in attendance at the zoning board hearing objecting to the project, the variance was granted. Those benefiting from the $2 million profit were the Governor and Dennis DiPrete, Dennis’s brother Thomas, a son-in-law of former Cranston Mayor James Taft. “A month later, the Texas developer received a state wetlands permit to develop another piece of land in North Providence. Dennis DiPrete had done some engineering work on that property, and state environmental officials later said they had been pressured by the Governor’s office to issue the permit.”

While publicly, the Governor issued an apology crafted by Doyle and another aid, Robert D. Murray, privately he was furious that he was forced to do so. All of this preceded the 1988 election that DiPrete won by a scant 2% of the vote.

Michael W. Piccoli Finds a Way to Expand the Governor’s Fortunes

In the midst of these investigations, police were given a tip to look into a “questionable sewer-construction contract in Cranston. The investigators found themselves on the trail of Michael Piccoli, a contractor from Smithfield. Within months, the investigators had built an overwhelming case that Piccoli had padded his construction bills in Cranston and paid kickbacks to Cranston City officials. The Investigators also found evidence that Piccoli had been wheeling and dealing at the state central landfill, which he had overseen as a DiPrete-appointed member of the board of the state Solid Waste Management Corporation. The authorities had Piccoli dead to rights. They invited him downtown for a conversation. After listening to the charges he faced, Piccoli said he would cooperate. ‘I can’t give you the Governor,’ he said, ‘but I can give you Dennis.’ ”

Michael W. Piccoli had been trying to become part of the “DiPrete contractor store” for years. As a principal in Piccoli & Sons, a paving company, he had tried desperately to get the attention of DiPrete. He was a political contributor going back to DiPrete’s mayoral days. He paved DiPrete’s driveway free of charge, served as a political fundraiser and helped erect “DiPrete for Governor” signs. This kind of activity was nothing new for Piccoli. Throughout the 1980s he made millions off the City of Cranston on sewer and other projects. In exchange, he paved the driveways of city officials, and in some cases, the relatives of city officials, at no charge. Certain court documents show that Piccoli signed a contract to pave a road. While the contract required the use of 4 inches of asphalt, Piccoli used only 2 inches. To protect himself against any backlash, Piccoli provided perks to the public officials. To one he gave money to take his family to Disney World. For another, he dug the hole in his backyard so the official could have a pool installed. The court records show that he even became upset when one city official had his driveway paved by another firm. Piccoli complained that he should have been given the opportunity to perform the favor. He took Mayor Michael Trafficante to the luxury box at Fenway Park, a perk worth about $4,000. Trafficante didn’t refuse. He took others golfing and still others were invited as his guest to his Florida condominium. It didn’t seem to matter to Piccoli that the taxpayers of Cranston paid the bill in the form of inflated contract charges.

While “DiPrete stumped the state promising an ethical revolution in government, Piccoli & Sons labored at the candidate’s house. Workers installed curbing, put in a new driveway, and resurfaced the tennis court.” The work took three days and despite the $7,000 to $10,000 cost indicated in court records, DiPrete paid nothing for the work.

For his loyalty to DiPrete, Piccoli’s reward came in the form of an appointment to the Board of Commissioners of the State’s Solid Waste Management Corporation, a quasi-public agency that owned and operated New England’s largest landfill in Johnston. He also received an invitation to join the exclusive Friends of DiPrete – the Governor’s campaign finance committee.

Perhaps most significantly, Piccoli had the opportunity to befriend Dennis DiPrete and the two began meeting routinely for lunch in some of the city’s finest restaurants. “According to Piccoli’s later testimony, Dennis DiPrete asked Piccoli to keep him informed of state work coming up at the Central Landfill; Piccoli told DiPrete of his own interest in state work. Piccoli told the Grand Jury that for state-landfill work, he had followed Dennis DiPrete’s directions on selecting contractors. His testimony also revealed that he had collected contractors’ contributions to Governor DiPrete’s campaign.”

Just four years later, Attorney General O’Neil was once again in that now too familiar position of dealing with accomplices in order to get the DiPretes. In a meeting with Piccoli, O’Neil recited the bad news; “there was evidence, said O’Neil, that Piccoli had been fleecing the taxpayers for years. In Cranston, he’d stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars, submitting false bills and bribing city officials; at Solid Waste, he’d used his position to shake down contractors. Piccoli sat in silence. The only time he betrayed emotion was when O’Neil told him his wife was also in trouble, for having apparently cooked the company books. The contractor’s face flushed. The attorney general brought up the state’s investigation of the DiPretes and asked for Piccoli’s cooperation. ‘I can’t give you the Governor,’ responded Piccoli. ‘But I can give you Dennis. Michael Piccoli pleaded guilty to taking $90,000 in bribes for state and Cranston-city contracts.’ ”

Piccoli testified that he would let staff of the RI Solid Waste Management Corporation know if the contractor in question was the choice of Dennis DiPrete by looking out the window toward the State House and nodding. Piccoli also arranged some of his own deals with landfill contractors. “One gave him $200 a week in cash, Piccoli later told investigators, which he put in his pocket for ‘walking around’ money. According to court records, Piccoli told a state-police detective that he once gave the Solid Waste Chairman, Richard A. Johnson, ten $100 bills, asking Johnson to cut him in on any deals he had cooking – ‘to become a player with me.’ ” Johnson testified that despite their friendship, he refused, and cooperated with authorities. Thomas Wright, the Director of the Solid Waste Management Corporation, said “Piccoli spent an inordinate amount of time at the landfill, meddling in the day-to-day operations, as well as contract negotiations.”

Indeed he did! In a story typical of Rhode Island’s small size and incestuous political nature, Paul Caranci, a co-author of this book, was employed by the Rhode Island Solid Waste Management Association as the organization Chief Property Manager at the same time that Piccoli was serving as its vice chairman. The primary role of the Chief Property Manager at that time was to implement the requirements of a state statute that required RISWMC to take by eminent domain all residential property located within a 1,000 foot radius of the landfill’s operational boundary, and to acquire by optional purchase, all the of the residential property located between 1,000 and 2,000 feet of the landfill’s operational boundary. This was a significant amount of land and was to cost the Corporation several million dollars. The controversial legislation was made necessary when the RI State Legislature, reacting to the odor and environmental complaints of landfill neighbors, many of whom purchased their properties long after the establishment of the landfill operation, passed the unfunded mandate.

In order to facilitate the mandate, Caranci drafted rules and regulations governing the program. These rules and regulations were advertised for public hearing in accordance with the provisions of the Administrative Procedures Act (APA). This lengthy process involves a public hearing, submission, acceptance and review of public comments, and a vote of approval by the Board. Once this was accomplished, the final rules and regulations were promulgated. The rules were written and approved to maintain the highest integrity in a highly visible and controversial project.

In accordance with the newly adopted rules and regulations, the RISWMC appraised the subject property using the services of certified appraisers selected through the competitive bidding process. Three were selected. Thomas Andolfo and his firm, Andolfo Appraisal Services, were contracted for the appraisal of developed residential land while William McGovern owner of Northeast Appraisal Services was selected to perform appraisals of vacant land. Bill Sweeney of Cooke & Co. Appraisal Services was contracted to act as review appraiser in the event that the Corporation’s appraisal was lower than that of the property owner. The property owner, therefore, was also urged to solicit his/her own appraisal by any certified appraiser other than the ones hired by the Corporation. The caveat was that the property owner had to have his/her appraisal complete and available at the time of the initial offer. The property owner and his/her representative(s) and the RISWMC’s team (consisting of Caranci, his assistant Patricia Cerbo, Arnold Johnson and Jeffrey Gladstone, the Corporation’s inside and outside legal counsels respectively, and the appropriate RISWMC appraiser) would then meet so that the Corporation’s offer could be disclosed. If the offer was acceptable to the property owner, the proper documents would be signed. If the property owner deemed the offer too low and had a legitimate appraisal that was higher in value, then his/her appraisal would be submitted. A review appraiser would be given the two competing appraisals and that appraiser would provide a final opinion of value. That estimate of value represented the final offer to the property owner. The final offer was binding in eminent domain cases while the property owner had the right to refuse the offer if the property were located between 1,000 and 2,000 feet of the operational boundary of the landfill. In order for the process to work fairly, it was critical that word of the value of the Corporation’s appraisal be maintained in the strictest confidence. Only the aforementioned members of the “team” knew the value prior to the offer being made to the property owner. If the property owner had advanced information of the value to be offered, he/she could simply pay an unscrupulous appraiser to provide a value higher than that of the Corporation assuring that the two appraisals would be sent to review.

One of the properties being taken by eminent domain was a unique property owned by one of Piccoli’s business associates. His property was unique in that in contained a grandfathered landscaping debris landfill and a tree farm. Piccoli tried relentlessly to obtain a copy of the appraisal report from the moment it was received. Despite Piccoli’s threats, Caranci would not disclose the appraised value which appeared to be high due to the unique nature of the property. Finally, on a Friday afternoon, when the pressure from the Board’s vice chairman became too much for Caranci to deal with, he notified RISWMC Director Thomas E. Wright of Piccoli’s intimidation tactics. Wright immediately contacted Board Chairman, Richard “Dick” Johnson, who apparently called Piccoli over the weekend and told him to back off. Piccoli was compliant but upset. Piccoli marched into Caranci’s office early Monday morning to let him know of his displeasure. Of course he did so in a non-descript way. “You did me a favor.” Piccoli said. “Now I cannot be accused of passing the information along to the owner.” As he began to walk away, he turned and said, “But I’ll remember this!” Caranci had momentarily derailed Piccoli's plan, but clearly there would be a price to pay for his perceived insubordination.

While Piccoli spent his days wining and dining and golfing with government officials, his employees and partners were getting impatient. “’Where’s the work?’ one of his brothers would holler in the office. ‘How come we’re not getting any work? Not to worry, Mike assured everyone. ‘A lot of gravy is coming.’ ”

The gravy came in 1989 with the addition to the state prison’s intake center. Dennis DiPrete told him “this one’s yours.” Piccoli’s firm was selected as the site’s main contractor charged with overseeing all site preparation and excavation work but could not post the necessary bond required of all firms that bid on state jobs. The job went instead to Laura Donatelli, the daughter of a North Providence contractor who, as a woman, qualified as a minority contractor.” Because her company owned no equipment, however, she hired Piccoli as a subcontractor. Despite having crews on site seven days per week for four months and running up labor charges of $20,000 a week, Donatelli paid him only $50,000, $350,000 less than he expected. He appealed to Dennis DiPrete to force Donatelli to pony up, but he never did collect.

During this time, Piccoli met with A. Robert Lusi, another Smithfield contractor. Lusi wanted Piccoli’s help in getting state jobs. Piccoli agreed to help. A few months later, Robert’s brother Gus identified the state job he was interested in; the URI job, a planned $600,000 expansion of the University’s Library. Both Lusis and Piccoli had a similar account of events during their Grand Jury testimony. “Piccoli told the investigators that he had reported the Lusis’ interest to Dennis DiPrete. A few days later, he recalled, DiPrete told him the URI contract would cost $60,000 – 10 percent of the $600,000 fee the Lusis’ stood to make. Piccoli, in his testimony, said that Gus Lusi’s response to the offer was ‘I’ll gladly give him the $60,000.’ In their testimony, the Lusi brothers said they had agreed to each put up $30,000. Robert Lusi kept his money in a safe deposit box at a Johnston branch of Fleet Bank; Gus Lusi kept his in his desk drawer….In the ensuing months, the Lusis paid $40,000 in kickbacks, including a $5,000 ‘finder fee’ to Piccoli. The sum also included a $10,000 campaign check to ‘Victory ’90,’ a DiPrete-sponsored Republican fundraiser featuring President George H. W. Bush (‘that was an extortion in my opinion,’ Gus Lusi later testified).”

Piccoli testified that he extracted some revenge for Dennis DiPrete’s failure to get Piccoli’s money from Donatelli for the prison job. When Lusi gave Piccoli an envelope containing $15,000 meant for Dennis DiPrete, Piccoli removed $5,000 and gave only the remaining $10,000 to Dennis. But Piccoli’s firm never could recover from the losses on the prison job. In the spring of 1991, The Providence Journal reported that Piccoli was unable to pay $9,000 in dumping fees owed to the landfill. He was forced to resign from the Corporation’s Board in disgrace. In December, Piccoli & Sons closed down. Piccoli’s home in Lincoln was sold and his Lincoln Continental was repossessed. He was even being trailed by a bookie for not paying several thousand dollars in gambling debts.

Financial problems notwithstanding, investigators would not let up. They were interviewing Piccoli’s former employees and issued a subpoena for all his business records dealing with Cranston. As a result of the information obtained, Piccoli “pleaded guilty to five felony charges. He admitted to crimes involving the state landfill, the City of Cranston, and Governor DiPrete’s administration. He was bound for prison – the only person in the DiPrete case thus far who has spent any time behind bars. A prosecutor recommended a lenient sentence, because of Piccoli’s pledge to cooperate. The sentence would later become a subject of controversy when lawyers for the DiPretes noted that the prosecutors had allowed Piccoli to pay just $135,000 in restitution to the City of Cranston – far less than the $1 million he admitted stealing from the city.” The Lusi brothers obtained immunity as a result of their testimony about the URI payoffs.