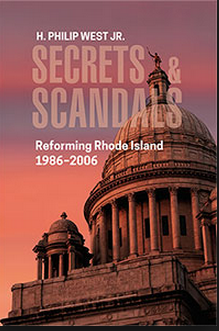

Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 35

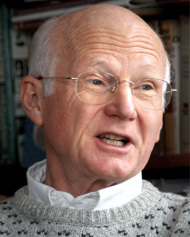

H. Philip West Jr.

Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 35

Since colonial times, the legislature had controlled state government. Governors were barred from making many executive appointments, and judges could never forget that on a single day in 1935 the General Assembly sacked the entire Supreme Court.

Without constitutional checks and balances, citizens suffered under single party control. Republicans ruled during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; Democrats held sway from the 1930s into the twenty-first century. In their eras of unchecked control, both parties became corrupt.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTH Philip West's SECRETS & SCANDALS tells the inside story of events that shook Rhode Island’s culture of corruption, gave birth to the nation’s strongest ethics commission, and finally brought separation of powers in 2004. No single leader, no political party, no organization could have converted betrayals of public trust into historic reforms. But when citizen coalitions worked with dedicated public officials to address systemic failures, government changed.

Three times—in 2002, 2008, and 2013—Chicago’s Better Government Association has scored state laws that promote integrity, accountability, and government transparency. In 50-state rankings, Rhode Island ranked second twice and first in 2013—largely because of reforms reported in SECRETS & SCANDALS.

Each week, GoLocalProv will be running a chapter from SECRETS & SCANDALS: Reforming Rhode Island, 1986-2006, which chronicles major government reforms that took place during H. Philip West's years as executive director of Common Cause of Rhode Island. The book is available from the local bookstores found HERE.

Part 4

35

Gifts (1997–2000)

The meltdown of the Ethics Commission may have begun at Fenway Park on Patriots’ Day in 1996. Terrence Murray, chairman of Fleet Bank, hosted lunch in his corporate box for Gov. Lincoln Almond, his wife, son, and three top staff members. They chatted about the ball game and plans for the bank’s expansion in Rhode Island. Almond agreed that the state would buy a building for lease to Fleet; Murray promised that Fleet would hire 350 people over the next two years.

Providence Journal reporter Bob Wyss later wrote that the tickets and lunches at Fenway had been worth $74 per person. His story ran on the front page just as the Ethics Commission began mulling ways to stop public officials from taking gratuities from “interested persons.” Readers knew Almond had little taste for luxury, but some took offense at his hobnobbing high above the ball field. Wyss listed other gifts that Almond had accepted: an academic robe and hood, framed lithographs and paintings, a rocking chair, medals, luggage, and items of clothing.

Wyss also described trade missions to Asia, Latin America, and Portugal. Marilyn Almond had traveled with her husband, her expenses covered by corporate donors who funneled their payments through the Rhode Island Economic Development Corporation.

Almond insisted that trade missions were vital to the state’s economy and were not intended as gifts to him. He promised to refuse any gift he felt was inappropriate, saying he would always err on the side of caution. When Wyss asked me about this, I mentioned that the Ethics Commission had warned against free travel for family members. I said I wished he had sought an advisory opinion first. The story reflected poorly on his judgment about gifts.

Legislative gratuities also raised eyebrows. Reporter Christopher Rowland calculated that Speaker John Harwood and Majority Leader George Caruolo had spent $50,000 wining and dining guests in pricey Providence restaurants. Lobbyists had contributed most of the money as campaign contributions. Caruolo described his and Harwood’s philosophy as, “If you can’t drink the lobbyists’ drinks and eat their food and then vote against them, you don’t belong at the State House.”

Gifts also flowed to municipal officials. The Journal reported that Johnston Town Council President Joseph R. Ballirano had accepted a flight to New Orleans and a ticket to watch the New England Patriots in Super Bowl XXXI. Louis Vinagro Jr., a notorious pig farmer and trash hauler, had paid Ballirano’s way while his $37,000 per month trash hauling and recycling contract was up for renewal. Ballirano claimed he had reimbursed Vinagro $1,800 in cash but quickly became the target of ethics complaints.

When subpoenaed, Ballirano could not document the expenses or his repayment. In the civil equivalent of a plea bargain, he negotiated a settlement, admitted violating the law, and paid a $4,000 fine.

Meanwhile, Providence firefighters filed an ethics complaint against their union leader, Stephen T. Day, who had accepted lavish gifts and entertainment from two money managers while he served on the city’s Retirement Board. In December 1997, the Ethics Commission had found probable cause that Day had accepted gifts on at least nineteen occasions between 1991 and 1995. While the money managers plied him with $3,393 worth of cocktails, lunches, dinners, and a hotel room, he steered more than $15 million to the funds they managed. Day had not reported these gratuities on his ethics disclosure forms.

During the winter and spring of 1998, the Ethics Commission began public hearings on a new gift rule for all public officials. One proposal would outlaw the common practice of accepting gifts from “interested persons.” The commission’s executive director, Martin Healey, explained that the federal government and ten other states had adopted similar rules.

Gov. Almond sent executive counsel Joe Larisa to testify that such a “zero-tolerance” rule would disrupt state business. Larisa claimed that the governor’s meetings with officials of the New England Patriots over their possible move to Providence would have been hampered if they had to split the cost of sandwiches. Larisa said Almond could support disclosure of food or gifts worth more than $50 but would oppose a complete ban.

At its first meeting in June 1998, after months of the public testimony and debate required under state law, commissioners brushed aside dire predictions and adopted a carefully crafted rule, a gift ban that many began calling “zero-tolerance.”

The second-guessing began instantly. Lobbyists and legislators mocked the proposed rule as nitpicking. William A. Farrell, who lobbied for associations of lawyers, bankers, insurance brokers, hospitals, and trash-haulers, told reporter Scott MacKay, “You’re not going to stop guys from Johnston from taking trips to the Super Bowl by passing some rules at the Ethics Commission.” Critics ridiculed zero-tolerance for banning cups of coffee, bologna sandwiches, or sticks of gum.

Without announcing a plan, Governor Almond and General Assembly leaders began replacing the Ethics Commission — not suddenly, but one appointment at a time. During deliberations on the gift rule, Almond appointed Melvin L. Zurier, a Harvard-educated lawyer and respected community elder, who argued against zero-tolerance and voted against its passage. Zurier had largely retired from Tillinghast, Licht & Semonoff but remained close to his colleagues, including former House Speaker Joseph DeAngelis, former Lt. Gov. Richard A. Licht, and top lobbyist Joseph W. Walsh.

The gift ban took effect in July 1998. Commissioner John O’Brien, a staunch supporter, reached the end of his term in September. In his eighties, O’Brien was grouchy, diligent, and incorruptible. He had served for decades as Providence district director of the Internal Revenue Service and chaired the old Conflict of Interest Commission during the ten years Rae Condon was its executive director. “If he hadn’t been at the helm,” Condon told reporter Maria Miro Johnson, the commission “probably would not have survived.” In 1987, when the old Conflict of Interest Commission gave way to the new Ethics Commission, O’Brien was appointed to the new panel and became vice chair. A fierce advocate for zero-tolerance, O’Brien called it absurd for public officials to quibble about the size of gifts. “It makes no common sense,” he growled, “when you take a public service job, that you’re also entitled to take gifts.”

Commissioners routinely served many months beyond their terms, but Almond had O’Brien’s replacement waiting in the wings even before his term expired. House Majority Leader Gerard M. Martineau had nominated James V. Murray, a staff attorney for Amica Insurance, whose two top lawyers were State House lobbyists. Almond appointed Murray in record time and later sent O’Brien a two-sentence form letter thanking him and wishing him well.

During the next year, the governor and legislative leaders, who nominated five members of the Ethics Commission, dismantled the panel of ethically alert individuals who had adopted the gift ban. Gone were a school administrator, an urban pastor, an accountant, a financial services manager, and a criminal defense lawyer. In their places were well-connected attorneys: Francis J. Flanagan, Thomas D. Goldberg, Richard E. Kirby, Robin L. Main, James V. Murray, and Melvin L. Zurier. While no strategy was ever announced, these six new commissioners zeroed in on the zero-tolerance gift rule.

In the spring of 1999, the Ethics Commission began exploring the ethics rules of other states that limited lobbyist contributions or banned campaign fundraising during the legislative session. Executive director Martin Healey asked that commissioners who were business associates of registered lobbyists disclose their relationships and recuse themselves.

Commissioner Thomas D. Goldberg was the law partner and brother of former Senate Minority Leader Robert D. Goldberg, who had become one of the state’s top lobbyists. Rather than step aside, Thomas Goldberg requested an advisory opinion.

Staff attorneys recommended that he not discuss or vote on rules involving lobbyists and legislators since his relationship — both as brother and law partner of a lobbyist — could affect his judgment. The draft hinged on differences between lobbyists. Some were paid well by commercial clients, but many others worked at low salaries for nonprofit groups or volunteered their time. The advisory cited sections of law and twenty-two previous advisory opinions. It declared that Goldberg should not “participate in the consideration of proposed regulations affecting the relationship between lobbyists and members of the General Assembly.”

Goldberg disagreed and brought an attorney to represent him. Kathleen Managhan argued that Commissioner Goldberg’s brother and law partner would not benefit any more than the other five hundred or more State House lobbyists. She insisted that his participation was protected under the “class exception” section of the law, under which lobbyists were a “significant and definable class.”

Healey disagreed, arguing that the draft advice to Thomas Goldberg matched opinions the commission had approved for other officials. He described the differences between classes of lobbyists.

Commissioner David McCahan, a retired insurance executive, argued that the Ethics Commission’s credibility depended on public perception that commissioners would always “avoid the appearance of impropriety.” With tears welling in his eyes, the 70-year-old McCahan reminded his fellow commissioners of their constitutional duty to rise above the bare legal minimum and exemplify the highest standard of ethics.

Richard Kirby disagreed, arguing that lobbyists were a significant and definable class. “When the law provides a class exception,” he declared, “it is neither unethical nor inappropriate for Commissioner Goldberg to invoke it.”

Amelia E. Edwards, the commission’s new legal counsel, asked a rhetorical question whose answer seemed obvious: “How can a brother represent his brother without a conflict of interest?”

No one answered.

Four commissioners, none of them lawyers, approved the advisory opinion that warned Goldberg not to participate, while three voted against it. Since under the law a valid advisory opinion required five affirmative votes, this split left Thomas Goldberg without an advisory and without legal protection against any ethics complaint that might be filed against him.

Beyond the wide windows of the commission’s eighth floor hearing room, clouds mushroomed into a spring squall. More ominous by far, pressure mounting within the Ethics Commission felt like the tension of tectonic plates that might produce an earthquake.

On June 1, Thomas Goldberg filed suit against the Ethics Commission on which he served. His petition stated that — despite the fact that his brother and law partner was a lobbyist — he sought clearance to make rules that would affect lobbyists. Although Goldberg conceded that staff lawyers and four of his fellow commissioners thought he had a conflict of interest and must recuse himself, three members did not agree. Without five votes he lacked a legally binding advisory opinion that would protect him against a complaint. He petitioned for a judicial ruling and wanted an injunction to delay proceedings until he received the court’s clearance to vote.

Tom and Bob Goldberg both sported neat mustaches. Both had broad foreheads and were going bald. Although they were roughly the same height, I guessed that Bob outweighed Tom by eighty pounds. Bob was extroverted, Tom shy. I suspected this was not the first time Tom Goldberg had been sent to fight his big brother’s battles.

I finally got to speak privately with him during a break. “Commissioner,” I said quietly, “you don’t need this. You can’t participate. It’s an obvious conflict.”

“That’s your opinion,” he shot back. “I disagree.”

That summer I assigned two college interns to comb through lobbyist reports. Far from finding a “significant and definable class,” as Tom Goldberg’s lawyer claimed, the data revealed real differences among the 774 registered lobbyists, depending on whether they served commercial interests, nonprofits, quasi-publics, or government agencies. Commercial lobbyists were typically well-compensated attorneys, and only twenty-four of them reported lobbying for three or more profit-making clients, trade associations, or unions. Rhode Island’s ten top-grossing lobbyists represented eighty-two clients, and their median income from lobbying in the 1999 legislative session appeared to be $125,250.

By contrast, a different class of lobbyists served as staff for nonprofit groups. Most worked for only one organization and attributed percentages of their salaries for lobbying. I reported $11,740 as lobbying income, a figure just below the median for the top ten nonprofit lobbyists.

The third group included government employees deployed by their agencies or quasi-public corporations to track legislation and promote their priorities. Many were lawyers with other duties in their agencies. The law treated agency lobbyists differently and did not require them to report compensation.

Campaign contributions dramatically distinguished commercial lobbyists from all the rest. Our interns found only one nonprofit lobbyist who had made a campaign contribution: $200 to John Harwood in the spring of 1999. Commercial lobbyists received huge sums and spread their largesse, mostly at spring fundraisers where ticket prices ranged from $75 to $150. The dates rose and fell along a bell curve that peaked between March and June, precisely when most bills passed or died. My mail typically brought two or three invitations each week — fundraising requests apparently sent to all registered lobbyists. I never donated to these groups and often sent personal notes explaining that Common Cause policy prohibited me from attending.

Far from being “no different from five hundred other lobbyists who are registered to work the State House hallways,” as Tom Goldberg’s lawyer had claimed, commercial lobbyists were in a class by themselves, and they contributed vastly more than their nonprofit counterparts. For example, at a single event — on the day before the House deadline for action on most bills — corporate and union lobbyists gave $102,550 to John Harwood. They also spent lavishly on dinners, sports tickets, and gifts to lawmakers. Entertainment expenses were costs of doing business; they could be itemized on tax returns but rarely appeared on lobbyist reports. Few doubted that such gratuities greased the skids.

In September 1999, our Common Cause newsletter listed the top ten commercial lobbyists, their clients, and their total compensation. We also named the top ten nonprofit lobbyists.

Within days of our publication, Dennis J. Roberts II, a former attorney general listed among the top grossing lobbyists, left a phone message that our figures were too high. “Tell Mr. West that if he can negotiate the fees reported in your newsletter, I’ll go halves with him.”

Sixth in our ranking of commercial lobbyists was Robert Goldberg, whose clients included companies that were fending off lawsuits over asbestos and lead paint, the gambling giant GTECH, the Smokeless Tobacco Council, and — ironically — United Healthcare. We reported his income from lobbying as $120,500.

Bob Goldberg phoned. “What the fuck is this?” he demanded. “Who says I made a hundred and twenty thousand dollars from lobbying?”

“Your lobbyist reports,” I said.

“You got it wrong!” he shouted.

“So what’s your figure?” I asked. “How much did you really make?”

“Figure it out yourself!” He slammed down the phone.

The confrontation troubled me, and I wished I had double-checked the data before we published. The lobbyist disclosure forms I completed each month were confusing, with spaces to report expenses, retainers, contractual fees, and agreed fees, but no line for salaries. I computed my lobbyist compensation as sixty percent of my salary during the legislative session.

Our interns had gone back to school, but Peter Hufstader pored through the documents they had photocopied. He noted ambiguities in the forms and different ways that lobbyists interpreted the questions. Lobbyist reports did not distinguish between amounts billed to clients and payments actually received. Confusion arose over contract fees that some lobbyists billed month after month as opposed to payments received only once. Hufstader compiled new estimates of what these lobbyists had received during the 1999 legislative session. As we had first reported, Democratic Party chair Guy Dufault earned $130,000, and Robert Goldberg remained one of the highest-paid lobbyists.

To set the record straight, I wrote to each lobbyist on our top ten list. I apologized for our error, promised a public correction, and asked each to confirm our revised estimate. Several called or wrote to agree with Hufstader’s revised numbers. Bob Goldberg did not reply, but we reported his income from lobbying as $100,500.

Hufstader and I met with Secretary of State Jim Langevin and several of his staff to share problems our study revealed in the lobbyist reporting forms. Langevin explained that his staff registered lobbyists, received their forms, time-stamped the documents, and made them available for public inspection, but no one compiled the data. He promised to revise the forms. Our October 1999 newsletter reported Langevin’s promise. We apologized for our errors and published Hufstader’s corrected numbers.

By the fall of 1999, most of the commissioners who had approved the gift ban in June 1998 were gone. Newly appointed lawyers now dominated the panel. They elected Melvin Zurier as chair and Richard Kirby, a protégé of John Harwood, as vice chair.

Former commissioner Mel Topf warned that the concentration of lawyers and politically connected commissioners had weakened the panel. What would happen, he asked, if the six lawyers had to recuse themselves from a complaint against a judge? I told reporters that the commission was being packed with politically connected lawyers who shared a commitment to overturn the 1998 zero-tolerance gift rule.

The formal process for administrative agencies like the Ethics Commission to amend rules was designed to be slow and transparent, with public notice required at least thirty days before a hearing. On October 26, I shared a slow elevator up to the commission’s headquarters with Brown University Political Science Professor Elmer E. Cornwell Jr., who was also the House Parliamentarian. I knew he was paid over forty thousand dollars a year to stand on the rostrum at the speaker’s elbow and interpret House rules. He and I had clashed publicly over separation of powers and the gift rule. Our small talk in the elevator did not diminish the distance between us.

On a table by the door lay alternate drafts of proposed gift rule revisions. Both versions would open the door for any public official to accept gratuities from any “interested person.” Commissioners were to choose among bracketed gift amounts to legalize: [$10 – $15 – $25 – $50 – $100 or less] [but in no case having an aggregate value of $50 – $100 – $200 – $500 in any calendar year]. One draft applied to meals, the other to gifts.

One at a time, witnesses walked to a small table that faced commissioners.

My heart sank as John Roney attacked the zero-tolerance gift rule. Roney had prosecuted our ethics complaint against Gov. Edward DiPrete in 1991 and won a Providence Senate seat in 1994. Now he claimed that the gift ban rested on an assumption that “people in public life are either so venal or so stupid that they need to be protected from those who would try to influence them by buying them a cup of coffee.” He argued that the rule was “demeaning to public servants,” that officeholders were subject to “tremendous burdens,” and that the rule made it difficult “to get good people to run for office.” Then Elmer Cornwell took the tack that the gift rule was absurd, unfair, and unenforceable. He insisted that a state representative would violate the rule by accepting a stick of gum from a lobbyist; he warned that the commission could prosecute only a few selective cases.

John Gregory lumbered toward the witness table. Only five years earlier, he had been an ally on the RIght Now! steering committee. Now president at the Northern Rhode Island Chamber of Commerce, he testified that the gift rule kept lawmakers away from chamber dinners they had previously attended. Asked what limits he thought appropriate, Gregory glanced at the bracketed amounts. He said the chamber wanted to entertain General Assembly members every year with a reception, a dinner, some lunches, and a golf tournament. He suggested an annual cap of $150 to $250 for each legislator in a calendar year.

The notion of legalizing a gift of $250 from each “interested person” left my brain spinning. If the Northern Rhode Island Chamber of Commerce was free to host 150 lawmakers at a dinner, what could stop every corporation that hired a lobbyist from treating legislators to dinners at the Capital Grille? Since the top ten lobbyists represented eighty-two commercial clients, would Bob Goldberg get a green light to take key lawmakers to separate dinners for each of his commercial clients?

In my turn to testify, I reminded commissioners that companies and trade groups had routinely plied lawmakers with meals and gifts before the 1998 zero-tolerance rule. I described a cozy dinner in 1986: only days before a key vote on federal credit union insurance, RISDIC officers bought drinks and dinner at the Aurora Club for the House Finance Committee. The committee then ignored Robert Stitt’s confidential report of looming dangers that RISDIC would collapse. The legislation they buried might have prevented the worst financial crisis in Rhode Island’s history.

In December, I wrote to Zurier on behalf of Common Cause with copies to each member of the commission, asking that they not amend the gift rule until conflicts of interest within the commission could be resolved. The gift rule, I said, aimed “to protect public servants and the public alike from the corrosive cynicism that permeates a culture steeped in periodic scandals.” For the first time in its history, a majority of Ethics Commission members were attorneys, and several worked at firms that deployed lobbyists. I added that we were not questioning their character or integrity, but several of them would have conflicts of interest if they voted. Only the most distorted reading of the law’s class exemption clause could conclude otherwise.

The following February, John Gudavich, an Operation Clean Government board member and a federal fraud investigator, urged the commissioners not to roll back its gift rule. Zero-tolerance was easy to understand and to manage, but relaxing the rule would tarnish the reputation of government officials in the eyes of the taxpayers. Gudavich argued that Rhode Island’s reputation for government corruption was one reason the state lagged behind the rest of New England in business expansion and job creation.

Sen. John Roney disagreed with Gudavich, charging that proponents of this rule wrongly equated “human commerce with corruption.” He favored revising the rule to allow $100 per occasion and a $200 limit per calendar year.

Joe Larisa appeared again on Almond’s behalf, testifying, “We didn’t think the gift ban was necessary, appropriate, or prudent in 1998, and we don’t think it is today.” He argued that most people saw no problem with a working lunch. “Business is discussed, and at the end of the day someone who may or may not be an interested party picks up the tab. And if public officials are swayed by that, we have a lot bigger problem in Rhode Island than the gift ban.”

In March, the commissioners began an internal debate that stretched through several public meetings. Commissioner James V. Murray proposed a new rule limiting gratuities to $150 on one occasion up to an aggregate $750 per year from any interested party. “I’m in favor of officials like the governor having access to people,” he said.

Commissioner Francis Flanagan, a former Navy JAG officer, said he favored $200 per event but with “an overall aggregate” limit of $1,000 per year from any one donor. “I’m a product of the restaurant industry,” he explained.

Robin Main agreed, suggesting that the commission not impose any “other type of cap, because I think we’re only creating an administrative nightmare.” She mused about a hypothetical case in which several Blue Cross employees might give a legislator gifts that added up to $40,000 from the same corporation.

Richard Kirby said he would favor $150 per event. “I reference a golf outing as a touchstone,” he said, “the cost with dinner and greens fees being approximately $150.” Kirby suggested a reporting requirement so that constituents could “see what their representatives might be doing on state business.”

Thomas Goldberg also favored a limit of $150 to $200. “I don’t need a bright line as to what’s reasonable,” he said. “I hope I have enough common sense and enough decency to do the right thing, and I think most of the public officials in the state do.” He wanted no overall cap on what officials could accept.

Commissioner James Lynch was incredulous. “I was waiting to have somebody convince me that what I previously thought was wrong,” he said. “I waited to hear any person tell me that they could not perform their job because the gift regulation prevented it. I didn’t hear that.” Seated behind the table in a business suit, Lynch retained his military bearing. “I have lived under gift regulations of this type for over forty years, and I had no problem with it. Did I like it? No. But it worked.” He urged his fellow commissioners to keep the gift rule intact. “I think that we’re going to open Pandora’s box by altering it in any of the fashions that have been mentioned.”

After remaining silent while younger and newer members spoke, David McCahan said he believed any change would be a major step backwards. “This commission came into being because of a perception and a reality of graft in government and the loss of confidence among people in their government.” Bald and pale, he spoke so softly that several of us in the audience cupped hands to our ears. He played off Kirby’s proposed touchstone of a golf outing. “What’s wrong with a legislator saying, ‘You know, Joe, I’d love to come play as your guest, but I want to be fair to everybody. I don’t want this to look bad. I just want to pay my own way. If you’ll let me come and let me know what my cost is to play in that golf tournament, I’d love to play with you.’”

Then the hearing bogged down over whether a change in the text would require more hearings.

Flanagan suggested new numbers for a gift rule: $150 per event with an annual limit of $750 per donor to any public official. He suggested that the rule require officials to report what they received, but not set an aggregate limit on what any official could accept. The newly appointed lawyers agreed.

Seats in the room filled quickly on May 23, the date scheduled for the final vote. Witnesses stood along the back and side walls. TV crews positioned cameras and placed microphones on the red-topped table. Commissioners entered and took their seats. Behind them, wide windows afforded a view over city rooftops toward Narragansett Bay. Chairman Melvin Zurier explained the process and called witnesses from a list.

Kevin McAllister introduced himself as a lawyer and president of Cranston City Council. He said that such an office made him subject to the commission’s regulations. “The regulations as they exist today make my job as a public official easier,” McAllister said. “They remove all the awkwardness and make it easier for me to maintain my neutrality. If I’m out at a public function or someone invites me for a drink, I can simply pay my own way. I say, ‘No, thank you, the Ethics Commission rule prohibits me from accepting a gratuity.’ Nobody’s feelings are hurt. It’s very easy, very simple.”

McAllister reminisced about working at the bar his parents owned. One patron would buy a drink for another, which created an obligation “to even things off ” by buying in return. Without mentioning Cranston’s former mayor, Edward DiPrete, McAllister described the struggle to clean up Cranston’s image. “Many of us have been doing our best to raise public perception of elected officials as honorable. The current regulation that prohibits accepting gifts makes our job easier — if we’re not encumbered by feelings that I owe this person.”

Nondas Voll described twenty-six grassroots groups that were members of the Fund for Community Progress, where she was executive director. She said those agencies struggled for environmental, economic, and social justice. To change the gift rule would hurt them because nonprofits could never compete in providing meals and gifts. She noted that members of Congress were limited to accepting $100 in meals for an entire year. “Why do we need $750 in Rhode Island?”

Richard J. Frechette, the chief financial officer from the Department of Corrections, said the zero-tolerance rule was an inconvenience, but also urged the commission to keep it. “We public officials haven’t had a good track record with common sense rules. I believe we are at a point in history right now where we have to follow absolute rules.”

Witness after witness — students, teachers, parents, religious leaders, business owners, retired public officials — all opposed the permissive new rule.

Only one witness gave credence to the proposed rule, attorney Michael A. Kelly, who served as counsel and lobbyist for Cumberland Farms convenience stores. He declared the zero-tolerance policy restrictive and unnecessary, using as an example the luncheon his clients hosted for local legislators, adding that they preferred not to wait around the State House and “chase their legislators down.” The lunch, Kelly said was “not anything elaborate. I think they served chicken wings and roast beef sandwiches.” He said the whole notion of zero-tolerance was “flawed and should be changed.”

A girl with long dark hair and glasses rose from where she had been sitting on the floor. She went to the witness table and introduced herself as Catherine Karner. “I’m in the sixth grade and twelve years old,” she said. “I came in fourth in the state geography bee.” She spoke of hard questions, like the capital of Burkina Faso, and easy questions, like which state had the highest ethical standards on gifts to public officials. “Today,” she said, “the answer is Rhode Island. How students answer that question tomorrow rests squarely on your shoulders.”

After the last witness, Zurier invited the commissioners to declare themselves. They followed judicial protocol, with the least senior member speaking first. Robin Main said she thought the gift rule was too extreme, but did not support the $750 top limit currently under consideration. She favored amending the draft rule to “achieve some balance.”

A second lawyer, Francis Flanagan, lambasted a comment I had made that the new gift rule would legalize bribery. He called this “mean-spiritedness” but suggested they lower the annual cap from $750 to $450 from any “interested person.”

James Murray, the third recently appointed lawyer, said if he had been on the commission when it approved the gift rule he would have voted against it. He told the crowd he appreciated their comments: “They have not fallen on deaf ears. I’m in favor of changing this regulation, but not at the amounts that have been proposed.”

Speaking from notes, Thomas Goldberg said zero-tolerance “reflects a belief that we can never have any faith in our public officials to carry out their duties responsibly and ethically. I think we can have some faith in our public officials.” He went on to defend himself against media stories criticizing his role in the debate. “During my tenure on this commission, I’ve had one hundred percent attendance at all commission meetings. That included advisory opinions, promulgation of rules, and adjudication of complaints. I have not hesitated to withdraw from my participation in matters I felt were appropriate for my disqualification. I do not believe that this amendment falls within that category. Believe me, the easiest thing for me would be to disqualify myself and walk away from this controversy. That would make my life a lot easier.”

His eyes found me in the crowd. “Finally,” he said, “I believe that many of the individuals who object to my participation would not object were I to be persuaded to vote against any amendment. I am convinced this criticism is intended simply to alter the result today, and it amounts to an attempt to improperly influence the deliberative process of a duly appointed Ethics Commission.”

Richard Kirby, the fourth recently appointed lawyer to speak, mentioned that he had phoned me twice to discuss the amounts specified in the proposed rule. He spoke without notes and made eye contact with people in the audience. “I want to thank you all for your really passionate argument and discussion about this,” he said. “I heard the comments about $750 being very, very high — a number that was shocking to a lot of people. I would be inclined to a lower number.”

David McCahan, the retired insurance supervisor, had taken close notes. He said he agreed with forty-seven of the forty-eight people who had testified, adding that several witnesses who held public positions had affirmed zero-tolerance. “‘It makes my job easier,’ they said. ‘Makes it easier to attract people into those kinds of jobs because they’re not beholden to some special interest.’” From his seat near the center McCahan spoke gently, focusing on the lawyers on the L-shaped ends of the table. “I urge you to think in terms of what zero-tolerance really means. I would urge you also in voting for anything other than zero-tolerance to think about what the message sends to your children and your grandchildren.”

Paul Verrecchia reminded his colleagues that he was chief of police at Brown University. He had served twenty-two years on the Providence Police and retired as a major. He declared himself against the proposed new gift rule. “I think the limits are unreasonable,” he said. “Another reason that I’m adamantly opposed to it is — even if the limits were reasonable — it does not put a limit on the total number of gifts that a public official can accept. So a public official under this regulation could accept a $750 limit per year from 100, 200, 300, or 5,000 donors.”

Verrecchia let his numbers sink in before pushing on. “Two years ago I voted against the zero gifts regulation. I felt that back then that it was not practical. I felt that it would hinder the operation of government to worry about whether or not a public official in a business meeting has to worry about paying for his or her sandwich.”

He asked whether a single rule could cover all public officials. “Do we want police officers accepting gifts? Do we want fire safety inspectors accepting gifts? Do we want building inspectors accepting gifts? Do we want health inspectors accepting gifts? Do we want people in enforcement and regulatory agencies accepting gifts from interested parties? I know I don’t, and those are more than rhetorical questions. I teach police officers that there is no such thing as a free cup of coffee.” He asked the commission to draft a rule that would go “beyond the legislature, well beyond the legislature.”

James Lynch, the retired army colonel, sat beside Zurier. Still sturdy in his late sixties, Lynch was unfailingly gracious. He said he had supported zero-tolerance three years earlier. “Since then, I’ve listened to everybody who complained, and there were many. I read the newspapers, I listened to the talk shows, and I attended every hearing on the gift regulation. I wanted to hear one person — just one person — tell me that they could not perform the function for which we are paying them because they cannot accept gifts. Five hearings, and I have yet to hear one individual tell me that they could not perform because they could not accept gifts.”

From his seat at the center Mel Zurier spoke last. “Unlike some of our critics,” he said, “I still believe after almost fifty years of being a lawyer that the legal profession is still honorable. That we lack some diversity on the commission by having six of our nine members who are lawyers may be a valid criticism, but it is not a valid criticism to question the motives or integrity of our members, whether lawyers or non-lawyers.”

Zurier explained why he had voted against zero-tolerance in 1998 and why he still opposed it. He spoke in the unhurried way of one who had dictated many letters, proposing a $50 cap on a working lunch or dinner and a $500 limit on the total any government official could accept from all sources in a year. “In sum,” he suggested, “I say let’s not move precipitously. Now that we’ve had the benefit of public input, we ought to have our staff and our legal counsel give us some new alternative draft embodying the matters that I’ve mentioned.”

He urged his colleagues to delay action because the rule as they had amended it now contained “very important deficiencies.” He noted that the version now before them implied that a public official “could demand or accept gifts of less than $150. And I’m sure that’s not the intention of any of you.” He said corrections were needed and asked for a motion to “take no further action on this proposal at this time.”

“Mr. Chairman,” Flanagan broke in, “with all due respect, I move that we accept the proposed regulation as modified with $150/$450.”

Kirby seconded instantly and added: “But, Mr. Chairman, if we’re going to amend this regulation, I would insist that it remove the words ‘shall ask, demand, or solicit.’ ”

Flanagan instantly accepted Kirby’s amendment.

Zurier and the commission’s legal counsel, Amelia Edwards, tried to parse the parliamentary tangle and requirements of the state’s Administrative Procedures Act. Edwards said any substantial change required that the amended rule be advertised again and considered after public testimony at a new hearing. Kirby was prepared for this and cited a federal case in which the nation’s highest court had opined that procedural rules were meant to ensure meaningful public participation, not to be a strait jacket for agencies.

Executive Director Martin Healey responded that Flanagan’s motion changed the rule substantially and triggered the requirement for another public hearing. Zurier asked for a vote to postpone, and the three most senior members — Lynch, McCahan, and Verrecchia — joined him in raising their hands. The five most recently appointed lawyers — Flanagan, Kirby, Murray, Main, and Goldberg — voted to push forward.

“Have we not been hearing?” Verrecchia demanded. “I’m at loss as to why we’re even considering $150, let alone $450. I think $450 is just as irrational as $750. There’s not even a total cap on the amount of gifts that any public official could accept. I’m not talking about the individual aggregate from each donor. I’m talking about total. The cap isn’t there.” He seemed perplexed, indignant, and vulnerable all at once. “I don’t see the logic. I think it’s totally ludicrous, and it’s not practical. And now taking the testimony we heard into consideration, voting for this regulation is a direct slap in the face to the people who came and testified.”

David McCahan asked how the commission could enforce the proposed new rule. “We’re just opening up Pandora’s box to do whatever you want, and that’s not right.” Lynch also urged those who favored the higher limits to reconsider. “Give the chairman and the rest of us an opportunity to revisit this and perhaps come back with something more workable.”

At the center of the table, Zurier seemed forlorn. “Whom will this cover?” he cried. “Will it cover the policemen? Will cases of wine or gift certificates be permissible under this? Can the aggregate number of gifts received in the course of a year be thousands of dollars or more?” He looked for some sign of compromise from the five lawyers at opposite ends of their table, who sat stone-faced.

Zurier hung his head. “I want to note my profound sorrow over the action that’s being taken,” he said plaintively. “I really regret this. I think that — years from now when we talk of the Ethics Commission — we’ll realize this was sort of like the Dred Scott decision. It’s a self-inflicted wound.” His reference to that 1857 U.S. Supreme Court decision deepened the sense of foreboding. The justices had ruled that Dred Scott and other slaves were not citizens “within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States.” Their decision propelled the nation toward the Civil War.

But Zurier’s warning was to no avail. Just before noon, the panel voted. Flanagan, Goldberg, Kirby, Main, and Murray carried the day. With their vote Rhode Island veered from zero-tolerance to the most permissive gift rule in the United States.

The crowd sat stunned but did not go quietly. As the panelists rose, someone in the audience shouted: “Shame! Shame on you!”

Richard Kirby tried to make his way through the crowd to a coatroom, but a white-haired woman blocked his way. “Shame on you, Mr. Kirby!” she declared to his face. “Shame on you!”

David McCahan, his eyes wet with tears, shook the hands of many who flocked to thank him. Ever the teacher, Peter Hufstader made his way to young Catherine Karner and her sister. Both had testified against gutting the gift rule. “Some civics lesson,” Hufstader said softly to them and their mother.

Tom Goldberg’s tie-breaking vote came as no surprise. In anticipation, I had drafted an ethics complaint against him. By coincidence the Common Cause state board had long been scheduled to meet that very evening, and I had emailed a draft complaint the night before.

The complaint listed what I believed were essential facts. Thomas D. Goldberg was the brother and law partner of lobbyist Robert D. Goldberg. Robert Goldberg had collected over $100,000 from eight commercial clients in 1999. By a 4 to 3 vote the Ethics Commission had warned Thomas Goldberg not to participate in gift rule changes. The law required five votes for a binding advisory. Without the protection of an advisory, Thomas Goldberg knew he was vulnerable to a complaint. During a year of public discussion, he had “persistently rejected” private and public requests that he recuse himself.

“As a member of the constitutionally-mandated authority on ethics for public officials,” I wrote, “Thomas D. Goldberg bears an extraordinary responsibility to comply with ‘the highest standards of ethical conduct, to avoid even the appearance of impropriety and not to use his position for private gain or advantage.’”

In seven motions Goldberg had provided the crucial tie-breaking fifth vote. “By participating in these discussions and votes,” I wrote, “Thomas D. Goldberg used his public office to modify the conditions under which commercial lobbyists, including his brother and law partner Robert D. Goldberg, could provide entertainment and other gratuities to public officials.”

The Common Cause board met just after five o’clock and went into closed session for only the second time I could remember. I passed out photocopies of the complaint. The board voted unanimously to file it and fifteen of us signed the document.

In sharp contrast to our complaint against Gov. DiPrete, this would be open. The next morning, I delivered copies to the Ethics Commission and reporters.

Several days later, after a State House event, Gov. Almond drew me into his office. “I’m troubled,” he said, “that the sides have hardened on this gift ban question. I always thought zero-tolerance was unworkable, but these new numbers are far too high.”

Almond asked if I thought we could undo the damage, and I explained to him why we could not. I had tried to reason with Tom Goldberg, first privately and then publicly. Four members of the commission had approved an advisory opinion warning Goldberg not to participate. Those four, including Mel Zurier, had pleaded for compromise, but the five most recent appointees — all lawyers — had forced the decisive vote. As a result Rhode Island now had the most permissive gift rule in the United States, and once Tom Goldberg cast his series of tie-breaking votes, Common Cause had no choice but to file an ethics complaint against him.

Towering over me, Almond was baffled. “So, have we passed a point of no return?”

“I think so, Governor.”

I explained that Goldberg’s majority on the Ethics Commission would circle the wagons around him. Even Almond, as governor, had no power to overrule them. The battle lines were drawn. No one knew how this would end.

He helped organize coalitions that led in passage of dozens of ethics and open government laws and five major amendments to the Rhode Island Constitution, including the 2004 Separation of Powers Amendment.

West hosted many delegations from the U.S. State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program that came to learn about ethics and separation of powers. In 2000, he addressed a conference on government ethics laws in Tver, Russia. After retiring from Common Cause, he taught Ethics in Public Administration to graduate students at the University of Rhode Island.

Previously, West served as pastor of United Methodist churches and ran a settlement house on the Bowery in New York City. He helped with the delivery of medicines to victims of the South African-sponsored civil war in Mozambique and later assisted people displaced by Liberia’s civil war. He has been involved in developing affordable housing, day care centers, and other community services in New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

West graduated, Phi Beta Kappa, from Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y., received his masters degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York City, and published biblical research he completed at Cambridge University in England. In 2007, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Rhode Island College.

Since 1965 he has been married to Anne Grant, an Emmy Award-winning writer, a nonprofit executive, and retired United Methodist pastor. They live in Providence and have two grown sons, including cover illustrator Lars Grant-West.

This electronic version of SECRETS & SCANDALS: Reforming Rhode Island, 1986-2006 omits notes, which fill 92 pages in the printed text.