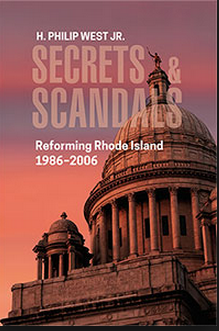

Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter Nine

H. Philip West Jr.

Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter Nine

DiPrete calibrated his answer, equivocating but not sounding defensive.

“Of course the statement refers to Norman DeLuca, my chief of staff. He is saying that we are not involved in the selection process and, to the extent of the meaning of the word ‘selection,’ that’s correct, As far as having a say in the recommendation to the director of administration? Yes, I did have input.”

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLAST“And you were certainly part of the selection process. Isn’t that correct?”

Kelly objected again and was overruled again.

“Not of the selection process,” DiPrete answered coolly.

Roney would not let him escape. “You had a role in the process pursuant to which the final selection for these contracts was made. Isn’t that correct?”

“I had a role which was restricted to a recommendation to an expression of opinion to the director of administration, who was free to accept or reject it.”

Another volley of objections rattled around the room.

DiPrete replied, “I was part of the process—in the sense of when a certain number of firms were deemed to have been qualified, the director of administration sent that list to me with only the names of the firms and the backup sheet on two or three as may be required with the amount of state business they had had since January 1, 1985. I tried to express an informed opinion when I could.”

Roney absorbed DiPrete’s run-on sentence. “So Mr. DeLuca’s statement—to the extent it refers to the governor’s office as not being involved in the selection process—is incorrect, is it not?”

After another objection from Kelly, Roney tried again.

“Did you ever, after reading this article, speak with Mr. DeLuca and say: ‘I have a role in this process’?” DiPrete smiled, the corners of his mouth still characteristically turned down.

“I don’t recall if I did or not. That was in the fall of 1988. It was a chaotic time of the year, I’m sure you’ll agree. I may have said something to him. I may not have. I honestly don’t recall.”

“Did you instruct Mr. DeLuca to issue any statement to the press about your role in this matter?”

“No, I don’t believe I did.”

Joe Kelly took his turn asking questions. DiPrete explained that he had issued the executive orders to establish a fair process for applicants. In response to the question whether he had made the final decision on architectural and engineering jobs, he answered unequivocally that he had not.

“Did you recommend Domenic Tutela because he gave you campaign contributions?”

“Absolutely not,” said DiPrete.

“When you made your recommendations, did you on occasions recommend people who hadn’t given contributions to your campaigns?”

“Sure did,” said DiPrete. “Yes.”

Kelly looked genuinely puzzled. “If a person makes a political contribution, are they automatically barred from bidding state jobs?”

“No,” the former governor said. “They’re not.”

“Is there anything in the law or the executive order that says people who make contributions can’t bid the jobs?”

“No, not at all.”

“Is there anything in that regulation that says those people are not qualified because they gave campaign contributions?”

“No,” said DiPrete.

“You testified that Mr. Tutela did get some state contracts, correct?”

“That is correct.”

“Mr. Tutela did not get this particular Olney Pond project, did he?”

“No, he didn’t get it.”

“And when you heard that Mr. Bendick of DEM wanted someone else your remark was: ‘Fine, he can have who he wants’?”

“That’s correct,” said Edward DiPrete.

Kelly led him through the differences between the words “recommendation” and “selection.”

DiPrete insisted that he did nothing more than express an opinion to Lippitt, who made the selection.

In his turn to ask questions, John O’Brien went back to parsing the executive orders. “Lippitt looks like the person that was going to select, but he had to send it up to you for a recommendation. You had set up a procedure that contravenes these two executive orders. Do you think the way this is worded gives the impression that you’re out of it? What do you think?”

DiPrete maintained eye contact with O’Brien and answered patiently: “It clearly spells out the procedures, but the governor is not out of anything. If something blows, even though there’s no executive order that says the governor should be involved in the loop, the chief executive is there, Mr. O’Brien.”

O’Brien scowled. “The executive order has nothing to do with what you’re talking about. It’s not even covered in the executive order. What you’re doing is circumventing the executive order.”

DiPrete stared back at him. “I respectfully disagree, sir.”

“That’s okay,” said O’Brien, his views clear.

At the end of questions about Olney Pond, DiPrete insisted that during eight years as mayor of Cranston, he had worked with Tutela and knew he was qualified. He rejected every suggestion that DEM’s team of scientists had any better basis for judgment.

After the hearing ended, Richard Morsilli left the room last and we shook hands. I risked a question about a brass plaque I had noticed not far from our home. The tennis courts in Roger Williams Park had been renamed for a young player killed by a drunk driver. “Commissioner,” I asked, “may I ask if you’re related to Todd Morsilli?”

“He was my son,” Morsilli said softly, his mournful eyes now focused on me. “Something happens when you lose your child. You absolutely cannot undo what’s happened. You either turn inward and start dying, or you open up and commit what’s left of your life to those positive things you can still do.”

He helped organize coalitions that led in passage of dozens of ethics and open government laws and five major amendments to the Rhode Island Constitution, including the 2004 Separation of Powers Amendment.

West hosted many delegations from the U.S. State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program that came to learn about ethics and separation of powers. In 2000, he addressed a conference on government ethics laws in Tver, Russia. After retiring from Common Cause, he taught Ethics in Public Administration to graduate students at the University of Rhode Island.

Previously, West served as pastor of United Methodist churches and ran a settlement house on the Bowery in New York City. He helped with the delivery of medicines to victims of the South African-sponsored civil war in Mozambique and later assisted people displaced by Liberia’s civil war. He has been involved in developing affordable housing, day care centers, and other community services in New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

West graduated, Phi Beta Kappa, from Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y., received his masters degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York City, and published biblical research he completed at Cambridge University in England. In 2007, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Rhode Island College.

Since 1965 he has been married to Anne Grant, an Emmy Award-winning writer, a nonprofit executive, and retired United Methodist pastor. They live in Providence and have two grown sons, including cover illustrator Lars Grant-West.

This electronic version of SECRETS & SCANDALS: Reforming Rhode Island, 1986-2006 omits notes, which fill 92 pages in the printed text.