Trump and Economic Statecraft - Mackubin Owens

Mackubin Owens, MINDSETTER™

Trump and Economic Statecraft - Mackubin Owens

Some years ago, I coined the phrase “the era of strategic happy talk” to describe the early 1990s, during which time U.S. policymakers bought into the notion that the world was on the cusp of a period of peace shaped by what Francis Fukuyama called the “end of history.” According to this view, the end of the Cold War marked the triumph of liberal democracy over communism. Having previously defeated fascism, the happy implication was that with no competing ideologies, liberal internationalism would prevail and, with certain exceptions, cooperation would supplant competition in international affairs. In this system, international institutions like the United Nations, the International Court of Justice, the World Trade Organization, the Paris Climate Accords, and even the pronouncements of the World Economic Forum would set the agenda for foreign relations.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLAST

Of course, some writers, such as the late political scientist Samuel Huntington and the splendid geopolitical analyst Robert Kaplan, warned that even with the end of the ideological struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union, there were still many things for countries to fight over. But for the most part, the end of ideological conflict plus the technological supremacy that the United States exhibited during the First Gulf War suggested that a challenge to a US-led liberal international order was unlikely.

This account is, of course, an oversimplification of Fukuyama’s thesis but many US policymakers acted as if its optimistic implications were true. That optimism influenced both Democratic and Republican administrations from the presidency of Bill Clinton until today. Even 9/11 was seen as an outlier: terrorism arising from radical Islamism was a threat to the periphery of the zone of great-power interaction but it could be contained as the great powers focused on trade and cooperation. The United States, regardless of whether it was governed by Democrats or Republicans, embraced the allegedly liberalizing influence of free trade and prioritized the protection of the “rules-based” postwar order.

But it seems clear that this system has failed to deliver on its promises. It has failed to prevent the rise of a hostile China or to prevent Russian or Iranian aggression. The Middle East is a bubbling cauldron. Domestically, free trade fundamentalism has led to a decline of American manufacturing and the attendant hollowing out of the American middle class. Indeed, Trump was re-elected primarily by those who have suffered from the economic dislocations caused by bad trade policy.

When it comes to trade policy, the worst offender has been the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In 2000, the optimism of the era of strategic happy talk led Congress to approve the China Relations Act, which granted permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) status (previously called the most favored nation) to China. But instead of adapting its behavior to the rules-based international order, China adopted an economic strategy of predatory capitalism. The PRC has upended global markets by refusing to adhere to the norms of liberal internationalism: employing massive government support for Chinese firms and ignoring environmental and labor standards. China uses currency manipulation, public-private partnerships, export subsidies, intellectual property theft, and slave labor to undercut production in other countries, ensuring that nobody else can compete with them. Accordingly, it has pulled one key American industry and supply chain after another into its orbit, eliminating millions of US jobs along the way.

China has also been able to exploit the West’s drive for renewable energy and net zero policy by claiming “climate leadership.” It’s a pretty slick trick. On the one hand, China produces more greenhouse gasses than all the developed countries combined. On the other, it uses the cheap coal that spews those greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere to produce solar panels and electric batteries that allow the West to indulge in the fantasy that modern economies can be powered by “green energy.”

Beijing also has employed its “belt and road initiative” (BRI) to advance its geopolitical situation by seeking a strategic foothold in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. Unfortunately for those countries that have been ensnared in Beijing’s infrastructure ambitions, the BRI—a neo-colonial approach focused on resource extraction and debt as a means of control—has proven to be a debt trap. BRI also permits China to exercise effective control of rare-earth minerals and technology.

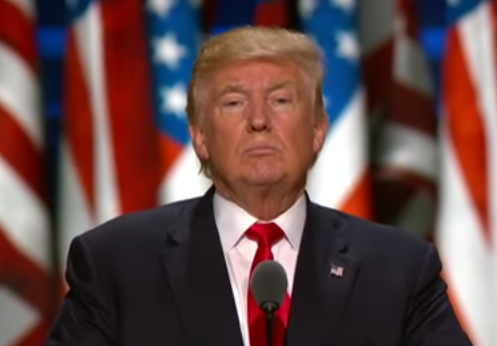

President-elect Trump has promised to use economic statecraft against China when he takes office. Indeed, the expansion of economic statecraft will be central to Trump’s foreign policy. The leading feature of this policy will be the imposition of stiff tariffs on Chinese imports, designed to return industrial production to the United States. Economists of all stripes tend to be critical of tariffs, which essentially constitute a tax on imported goods, and certainly, in a world economy characterized by free and open trade, tariffs distort markets to the detriment of parties to the exchange. But China’s predatory trade policies are hardly “fair.” Accordingly, even many Democrats are increasingly open to Trump’s approach, to include supporting legislation aimed at boosting US industrial production, e.g. the US Innovation and Competitiveness Act.

As one who has taught and written about economics and economic policy, I understand the shortcomings of tariffs and other forms of economic pressure. I would prefer a true free-trade regime, designed to maximize the efficiencies of the market by exploiting such elements as comparative advantage and specialization. But in an imperfect world, market fundamentalism must give way to prudent economic statecraft of the sort that maximizes US national interests in a world where control of markets, resources, technology, and military power matters.