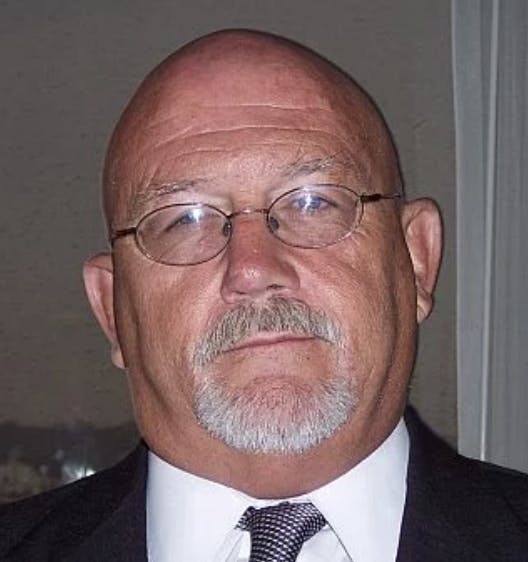

Russia, Ukraine, and Strategic Sobriety - Mackubin Owens

Mackubin Owens, MINDSETTER™

Russia, Ukraine, and Strategic Sobriety - Mackubin Owens

Why did Putin invade when he did? Why didn’t he strike when Trump was in the White House? The answer is that during Trump’s presidency, some important conditions prevailed: first, US energy policy kept world oil prices relatively low, to the advantage of both American citizens and our allies but to the disadvantage of Russia. Trump did so by ramping up U.S. domestic energy production by exploiting the technical revolution associated with hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and directional drilling, which transformed the United States into a net exporter of energy. As such, the United States was able to undercut Russia’s ability to use energy to blackmail Western and Central Europe and reduce Russian energy revenues.

Second, the United States took decisive steps to deter our enemies, rather than appeasing them as we had during the Obama administration. The Trump administration sold Patriot Missiles to Poland and provided lethal arms to Ukraine. It extricated the United States from an unfavorable arms control agreement with Russia. There was no Obama-era Russian “reset” or an Obama promise to be more “flexible” after his reelection in 2016.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTOf course, that was then. But now, confronted with a fait accompli, what do we do? Sound foreign policy requires strategic sobriety, guided by prudence: the examination of the means available in light of the ends one seeks. This means answering these questions: what are the US interests at stake? What are the courses of action available? What are the risks associated with the various courses of action? What is the likelihood of success?

Our strategic interests in Europe do not embrace Ukraine. While for strategic and cultural reasons, we expanded NATO after the Cold War to include the Visegrad States of Central Europe (Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia), Eastern Europe was and remains a “bridge too far.” Even if our interests did extend to Eastern Europe, geographical realities—“the tyranny of distance”—would severely limit direct military action by the United States. The likelihood of success of such action is low and the risk is high. Ukraine’s entire northern and eastern border is Belarus, a Putin ally, and Russia itself. The United States has placed US troops on alert and deployed some toward Russia, but what they can do is in question. Even the use of allied air power would be problematic.

Our NATO allies have demonstrated little stomach for going to war over Ukraine. They seem to regard a war on behalf of Donetsk and Luhansk the same way that Otto von Bismarck felt about war in the Balkans: not worth the healthy bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier.

Some have called for active US support of a guerrilla war against Russia. But Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv lies just south of the border with Belarus. Putin can achieve his strategic objective by a rapid seizure of the capital and the installation of a puppet regime. There is no strategic rationale for Russia to drive beyond Kyiv. The last thing Putin wants is to get bogged down in the Ukrainian hinterlands to be bled white in a guerilla war.

What about non-military courses of action? There are sanctions, of course, but their likely impact is limited. Unfortunately for US non-kinetic responses, the Biden administration has substantially weakened our greatest non-military tool against Russia: energy. Biden’s war against US domestic oil and gas production has been both an economic and foreign policy boon for Russia. Indeed, as noted above, it is unlikely that Putin would have invaded Ukraine had the United States continued to wield the energy club.

The unfortunate fact is that our short-term options on behalf of Ukraine are severely limited. The best we can do is try to mitigate the suffering of the Ukrainian people while punishing Putin’s Russia to the greatest extent we can. However, at this point, we need to recognize the constraints that geopolitical reality imposes on our choices.

But in the long run, we can learn geopolitical lessons and correct our mistakes. Lesson one is that weakness and indecisiveness invite aggression, especially by aggressors who are willing to take risks. We can minimize the likelihood of future aggression by Putin—or others—by taking decisive action to enhance US power, starting with unleashing domestic energy production, ramping up defense spending, and reinvigorating NATO under US leadership.