Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 15

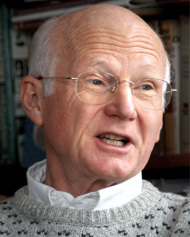

H. Philip West Jr.

Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 15

Since colonial times, the legislature had controlled state government. Governors were barred from making many executive appointments, and judges could never forget that on a single day in 1935 the General Assembly sacked the entire Supreme Court.

Without constitutional checks and balances, citizens suffered under single party control. Republicans ruled during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; Democrats held sway from the 1930s into the twenty-first century. In their eras of unchecked control, both parties became corrupt.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTH Philip West's SECRETS & SCANDALS tells the inside story of events that shook Rhode Island’s culture of corruption, gave birth to the nation’s strongest ethics commission, and finally brought separation of powers in 2004. No single leader, no political party, no organization could have converted betrayals of public trust into historic reforms. But when citizen coalitions worked with dedicated public officials to address systemic failures, government changed.

Three times—in 2002, 2008, and 2013—Chicago’s Better Government Association has scored state laws that promote integrity, accountability, and government transparency. In 50-state rankings, Rhode Island ranked second twice and first in 2013—largely because of reforms reported in SECRETS & SCANDALS.

Each week, GoLocalProv will be running a chapter from SECRETS & SCANDALS: Reforming Rhode Island, 1986-2006, which chronicles major government reforms that took place during H. Philip West's years as executive director of Common Cause of Rhode Island. The book is available from the local bookstores found HERE.

Chapter 15: Keeping Score (1992)

Politics has always been a game of smoke and mirrors. The RISDIC scandal and political machinations of two General Assembly sessions that followed had left many Rhode Islanders confused. Which legislative factions could they trust? Were the reform groups any better?

Our midsummer challenge was to pick through the legislative detritus and create a scorecard that would show voters how their senators and representatives actually performed. Bill Colleran, our resident rocket scientist, came to help. In the final hours of the 1992 legislative session, nearly every member of the General Assembly had voted for the bountiful crop of reforms that were now law.

“So were they holding their noses?” Colleran asked.

“Not visibly,” I said, “but if they’d had secret ballots, I think we’d have lost.” On the table before us lay piles of House and Senate journals, daily records that contained every legislative vote cast during the two-year term.

“So all we need to do,” Colleran observed wryly, “is reduce words to numbers.” An engineer by training, he had calculated orbits and trajectories for NASA and believed that anything worth thinking about could be presented in digital form.

His wife Julie, a high school English teacher, was equally committed to the project. “You know these senators and reps,” she said. “You know the bills and amendments they voted on. All you need to do is tell us which votes really mattered.”

That was easier said than done. We had no way to score the death of bills that legislative leaders routinely buried in committee to protect their troops from having to cast awkward votes on the floor.

The Collerans constructed spreadsheets to tally House and Senate votes, with legislators’ names filling the left-hand columns. For each vote they would list the bill number, date, and page in a House or Senate journal. Beneath that identifying data, they would use three columns: one for votes we considered pro-reform, a second for votes we took as anti-reform, and a third for absences. “Everybody gets a ‘1’ in one of those three columns,” Colleran said. “By adding the columns vertically, we check our totals against the journals. By adding rows horizontally, we compute the grades for each senator or representative.”

We would compute votes on campaign finance, ethics, and four-year terms that RIght Now! had promoted. We would also tabulate votes on redistricting, lobbyist disclosure, and judicial selection that Common Cause had pushed without RIght Now! support.

“That’s a lot of data entry,” Colleran said, “but it’s ultimately foolproof. If somebody challenges your numbers,” he quipped mischievously, “you unroll your spreadsheet and show how he voted on any particular bill. You’ll even have reference to a specific page in the House or Senate journal.”

I nodded. My first task would be to pick votes that tracked each bill’s travel through the House and Senate. We would count bills both from 1991, when few bills passed, and from 1992, when many became law.

“Here’s the deal,” Colleran said. “You give us the identifying information for each vote. I’ll create the formulas. Julie and I will enter the data and double-check for accuracy.”

I immersed myself in the journals and made notes. A week later, the Common Cause executive committee reviewed my list. I suggested that — except for Jeff Teitz’s campaign finance bill, which wove together many previous bills — we count votes for only one amendment and final passage of each bill each year in each chamber. The executive committee agreed on thirty-two votes in the Senate and thirty-three in the House of Representatives.

Bill Colleran explained how important it was to agree on all the votes before he and Julie started entering data. “We need to make clear to friend and foe alike that we’re not skewing numbers to hurt or help particular legislators.”

As their data accumulated, patterns formed before my eyes. Some senators did well in 1991 but plummeted in 1992. All were supporters of former Majority Leader David Carlin, who scored 91.7 percent in 1991 but only 66.7 percent in 1992. Bill Irons scored 100 percent the first year but dropped to 73.7 percent the second. John Bevilacqua, by contrast, scored 53.8 percent in 1991 and went up to 68.4 percent in 1992. Tom Lynch improved from 53.8 percent to 73.7 percent. Even Gregory J. Acciardo, who had taunted Bishop Hunt about nepotism, rose from 46.2 percent to 77.8 percent in 1992.

On the House side, Jeff Teitz raised his score from 80.0 percent in 1991 to 91.7 percent in 1992.

Colleran followed my finger on the screen. “That’s a big difference from Clean Sweep putting Teitz at the bottom of their scorecard,” he mused. “Look at my rep.” He pointed at Rep. Mark Heffner from Barrington. “He drops from 83.3 percent in ’91 to 59.5 percent in ’92.”

A quick look showed that Heffner supported Teitz’s comprehensive campaign finance bill in 1991 but voted — only a year later — for radical amendments that might have doomed the same bill. Teitz’s bill cut the top allowable contribution to each candidate from $2,000 to $1,000 a year, but Heffner supported a 1992 Clean Sweep amendment that would have slashed the allowable individual contribution in half again, to $500. Reducing contribution limits so drastically would have put challengers at an overwhelming disadvantage.

“You warned them, didn’t you?”

“We did,” I said. “With memos to each representative. And I spoke to many myself.”

“Did they really believe those amendments would improve campaigns?”

“Some probably did. We warned them that adding new amendments and sending Teitz’s bill to the Senate a second time would have prevented its use for the 1992 elections. And might have killed it entirely.”

Colleran stroked his mustache. “I don’t see how we can overlook those realities. Giving them a pass on those votes might make some look better, but it would be dishonest. Maybe,” he mused, “you just post their grades and let them explain to their constituents. We could also mark them on a curve.”

He quickly produced a formula that filled an additional column beside the names of all 150 members of the General Assembly. “This formula is exactly the same for everyone,” he said. “No special breaks or penalties.” With a click, he turned the formulas into percentages. Every score rose. Colleran’s final percentages lifted the Senate average to 75.4 percent, the House to 76.5 percent. “You might say these numbers reflect their real commitments,” he said. “For different reasons, many barely passed.”

I spot-checked the final percentages his curve formula produced against several I believed were committed to reform. Jim Langevin of Warwick came out on top with a score of 92.1 percent. Jeff Teitz came close behind with 89.9 percent, and Frank Gaschen had 89.2 percent. On the curve, Mark Heffner’s score rose to 81.4 percent.

I asked Colleran again if he used the same formula for all of them.

“Exactly the same delta factor from top to bottom. We’re counting every vote you described, and we’re giving everybody a mathematically consistent benefit of a doubt. That’s how you mark on a curve.”

I knew he was right but asked how these relatively low grades meshed with the fact that legislators had eventually enacted virtually the entire RIght Now! platform.

“We used data from two years,” he observed. “In 1991, even after RISDIC, they passed almost nothing you proposed. Isn’t that right?”

I nodded. In fact, over three or four years many of the same legislators had buried these proposals in committee.

“Do you think these figures are lying?”

I knew they were not. We decided to publish our legislative scorecard with an explanation to guide voters through this welter of information. I wrote that no scorecard could discern legislators’ motives — we could not judge the difference between a sincere vote for a radical amendment and mere grandstanding. I added that Common Cause never endorsed or opposed candidates for public office, and urged voters to use our legislative scorecard and those of other groups with great care.

We bundled lists of senators and representatives by regions of the state with comments on specific votes they had cast. We faxed press releases with legislative scores to newspapers, television, and radio stations.

As we hoped, newspapers listed senators and representatives in their regions in our ranked order of their support. Reporters picked up key differences between the Common Cause rankings and a second report card from Operation Clean Sweep. The Providence Journal noted “a distinct split in the reform movement,” suggested by the fact that “Rep. Jeffrey J. Teitz, D-Newport, finished last in Clean Sweep’s rankings of the House. But in Common Cause’s rankings, Teitz was fifth from the top.”

A Journal editorial on “the ratings game” urged readers against any “automatic acceptance” of candidates based on scorecards. Although the editors urged readers to learn about the groups that issued scorecards, they affirmed Common Cause’s values “and strongly supported the landmark ethics reform agenda it successfully advocated in the General Assembly this year.”

Several lawmakers or members of their families phoned our office to grouse about the scorecard, and others complained in person. One crisp fall evening I drove to the King Philip Inn in Bristol to address the Bristol County Chamber of Commerce at its annual meeting. I had forgotten that Sen. Richard M. Alegria, a member of the Bevilacqua faction, owned the hotel. Even after we curved the grades, Alegria ranked at the bottom of the Senate.

While chamber members were enjoying cocktails, I strolled the dining room and left copies of our scorecard on each table. As I walked back to the reception, I ran into the hulking Alegria as he proffered his election materials to dinner guests. His powerful grip almost crushed my hand. He pulled me close and growled in a voice barely above a whisper, “So you think I’m a bad person.”

“No, Senator,” I forced a smile. “I don’t think you’re a bad person, but we disagree with a lot of your votes.” I took his flyer and escaped into the convivial crowd. Later, I read Alegria’s handout. In a bulleted list of accomplishments he claimed to have been a leading advocate for ethics reform.

With their deep suspicion of government, Rhode Island voters had nixed four-year terms three times since the 1973 Constitutional Convention first recommended that change. The most recent rebuff came in 1986, when a proposed amendment would have granted quadrennial terms to both legislators and general officers. Fifty-nine percent of voters nixed the amendment. Our 1992 Question One would establish longer terms only for statewide general officers and would add a recall provision. Would these differences change the outcome?

The opposition to Question One was fragmented. Organized labor seemed to believe it could defeat four-year terms without spending much money. The state AFL-CIO Executive Council launched a wave of mailings that urged roughly eighty thousand current and retired union members to vote no. The ACLU, Government Accountability Project, and Reform ’92 all came out against Question One, but they had no money for TV or radio commercials.

One opponent enjoyed unlimited airtime. Moe Lauzier, a Libertarian talk show host on WHJJ-AM, dominated the afternoon commute. “How dumb are these do-gooders?” he inveighed. “Not only should those ninnies not get four-year terms! We should roll them all back to one-year terms!”

I turned into one of Hasbro’s parking lots for a meeting of the RIght Now! steering committee. Of a dozen major manufacturers that once provided steady blue-collar jobs for generations of workers, only the Hassenfeld brothers’ toy company still operated its worldwide business from Rhode Island. At the security desk, I signed in and clipped a visitor’s badge on my lapel. Departments along a wide corridor overflowed with bright color. The scent of freshly brewed coffee met me before I stepped through sleek modern doors.

Our agenda was the campaign for four-year terms. Seated beside Alan Hassenfeld at Hasbro’s board table, David Duffy passed out packets. “I have some polling data from the Becker Institute,” Duffy said. Each page of the stapled document held a single question with responses graphed in wide, boldly colored bars. “The bad news, “ Duffy said, “is that we’re losing. The good news is that as people get more information — like the fact that they could recall a governor — the more likely they are to vote yes on Question One.”

“It’s a tough sell,” said B. Jae Clanton, executive director of the Urban League. “You know that when white America gets a cold, the black community catches pneumonia. RISDIC caused deep wounds that haven’t even begun to heal. Whether people will even vote is an open question.”

Hassenfeld asked if people served by the Urban League were talking about four-year terms.

“None that I’ve heard,” Clanton said. “They wonder what’s the use.”

Jim Miller said many pastors understood the need for sound governance. “They may not have thought much about four-year terms for governor, but they know it often takes several years for a new preacher to learn the ropes. They get giving the governor four years to deliver.”

I passed out flyers that would be distributed in church bulletins on Sundays before the election. The Girl Scouts, Clean Water Action, the Sierra Club, the League of Women Voters, and Common Cause had begun distributing several hundred thousand of these in neighborhoods.

Thomas J. Skala, the president of Fleet Bank, studied the flyer and nodded his approval. Skala’s company had been absorbing institutions formerly insured by RISDIC. “Fleet couldn’t take a partisan position,” he said, “but I would distribute a well-designed informational piece on four-year terms.”

Dave Duffy — whose firm had created both RISDIC’s “carved in stone” commercial and the RIght Now! logo — offered to prepare a version of our brochure in plain vanilla language for bank customers and employees. “Four-year terms is about as nonpartisan as you can get,” Duffy said. “Constitutional reform doesn’t help any one politician or party.”

Alan Hassenfeld suggested that employers in the various chambers of commerce stuff information pieces into pay envelopes. “With all of our chambers,” he said, “we could achieve fairly wide distribution.”

The smell of printer’s ink permeated the Common Cause office. Boxes of flyers were stacked high between windows and near the door. Our mission was to convince voters that the proposed Four-Year Terms Amendment would create a more professional executive branch under less constant pressure to raise money for the next election.

Business leaders donated funds to pay three organizers who would disseminate flyers and train grassroots groups to promote four-year terms. Suzette Gephard, the former League of Women Voters president, had run for Congress but lost in the primary to David Carlin. Bob Cox had worked with the Rhode Island Council of Churches, while David Leach knew the inner workings of the Jewish Federation and its member groups. All three hit the ground running. They organized local groups to distribute leaflets at art fairs, fall festivals, farmers’ markets, and outside supermarkets.

During the fall of 1992, I crisscrossed Rhode Island, seeking support from the editors and publishers of the state’s five daily newspapers and the half-dozen small-town weeklies. My road atlas fell apart as I navigated back roads to out-of-the-way hamlets for meetings of chambers of commerce, church groups, art clubs, and societies named for Narragansett chiefs. I enjoyed the energy of the crowds as I preached the gospel of political reform. I thanked audiences for participating in RIght Now! rallies and trekking to the State House during the session. I reminded them that the Rhode Island Supreme Court had helped the cause of reform with its unanimous June 10 ruling that the Ethics Commission had power to write and enforce ethics rules for all public officials. Televised RISDIC hearings had added pressure for landmark campaign finance and ethics laws. But I told them grassroots calls had gotten this done. “Senators and reps kept telling me their constituents were after them wherever they went.”

I said we still had unfinished business. RIght Now! saw reform as a three-legged stool. Two legs — campaign finance reforms and the new ethics laws — were in place, but to make it sturdy we needed the third leg in the form of four-year terms for the governor and other statewide officers. Furthermore, we could learn from the experiences of other states. During the last forty years, twenty-eight states had amended their constitutions to establish four-year terms for their governors. No state that established four-year terms had reverted to two year-terms. Only three states still clung to two-year terms: Vermont, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island.

I asked whether Rhode Island could afford to keep its governors on a fundraising treadmill. Bruce Sundlun had poured out $4.1 million of his own money to beat Ed DiPrete for a two-year term. By contrast in neighboring Massachusetts, also in 1990, William Weld spent only $3.8 million to win a four-year term. Weld had faced the challenge of reaching five times as many voters in three costly media markets, including Boston. On a per capita basis, Rhode Island’s 1990 gubernatorial campaign was the second most expensive in the entire country, second only to Alaska’s, where candidates faced high media costs and had to campaign in planes across vast distances.

Listeners often asked when the first four-year election would take place. “In 1994,” I replied, “midway between presidential elections.” I said we hoped non-presidential contests would concentrate attention on state races.

When people asked about the two-term limit, I said RIght Now! had followed the federal model that limits American presidents to two four-year terms. Eight years and out would prevent anyone from becoming governor for life.

In answer to questions about how a governor or other general officer could be recalled, I explained that we did not want recall simply because a governor took an unpopular stand. Launching a recall would require some credible indication of wrongdoing: an arrest for a felony, conviction of a misdemeanor, or a finding of probable cause by the Ethics Commission.

“STRICTLY PRIVATE,” warned the sign on the wire gate at the edge of a North Kingstown forest, “Hebb Waterfowl Trust.” Gus Hebb had become a mainstay at Common Cause. His white-hot rage against corrupt officials rarely cooled. The wealthy industrialist had rejoiced when the Ethics Commission fined former Gov. Edward DiPrete $30,000; he reveled when the business community rallied under the RIght Now! banner.

Hebb had phoned to invite me. He swung the gate open and waved me onto a dirt road that led through a stand of towering pines. As he strode ahead of me, a long-legged bird marched possessively at his shoulder. A moment later, he introduced us. “This is Gertrude. She’s a Sandhill crane. She imprinted on me when she hatched, and she thinks I’m her mother.”

Gertrude stood as high as my shoulder and eyed me over a sharp beak, unperturbed by the cloud of cigar smoke that Hebb said would protect us from gnats. Few would guess that this rustic figure with his stogie, unlaced work shoes, and broad-brimmed hat was the president of a company that fabricated steel and aluminum for major construction projects.

As he showed me around, rare ducks waddled away. A sturdy steel structure stood incongruously in the woods. Gertrude and I followed him into shadows beneath its black framework, where we climbed a steel stairway into bright sunshine and gazed out on a series of interconnected observation decks.

“I call it ‘Treetops,’ ” Hebb said. “I’ve been building it for twenty years with leftovers of buildings and bridges. You could put three hundred elephants up here, and it wouldn’t budge.”

Trees rose through openings and around the edges. Below the railing, a herd of diminutive deer with great racks of antlers galloped toward a pond. Even the adults sported fawnlike spots. “They’re fallow deer,” he said. “Probably evolved in what’s now Iran and spread to Europe. Aren’t they gorgeous?”

Miniature deer with pronghorns and black facial markings paused below us and peered up, as if expecting to be fed. “They’re ‘muntjacs,’ ” Hebb said. “That means ‘barking deer.’ People are starting to keep them as pets, but they belong in herds and this is the only herd in New England.”

Hebb led me across the platform and pointed at the most regal birds I had ever seen. “Those are East African crowned cranes,” he said with obvious pride. Gold bristles framed their heads like haloes; their faces were stark black and white panels with brilliant red accents. “We made them comfortable enough to mate here. When we go down, I’ll show you their chicks.”

From another spot at the rail he pointed to his most endangered bird. “It’s called a ‘nene,’ ” he said. “They’re related to Canada geese, but they evolved and flourished on the Hawaiian Islands before sailing ships arrived with rats and cats and pigs.” He said nenes had plummeted to the edge of extinction.

I had never seen this tender, protective side of Gus Hebb. “I’ve been building my wildfowl refuge to protect and propagate these endangered species,” he explained. “I designed these treetop platforms to let people view my rare birds without disturbing them.”

He relit his cigar and inhaled. “In all these years, I’ve never brought people in. Never felt we had the occasion.” He blew a cloud of smoke. “Now I do. I’d like to host a celebration up here in the treetops.”

I sensed where he was going but waited for him to finish.

“What you and Alan Hassenfeld have done for this state is just beyond belief. I never thought I would see it in my lifetime.”

I thanked him and said we were not finished.

“Never will be,” he agreed. “But what an amazing start.” He offered to host a celebration, an October Sunday brunch with boxed lunches and champagne.

Gertrude and I hung on his every word. “That’s wonderful,” I said. “I’ll find out Alan’s schedule.”

Natalie Joslin mobilized our board and advisory council to plan the biggest party of her life. She formed a working committee and an honorary committee to promote what everyone quickly began calling “the Hebb Event.” The Providence Sunday Journal ran a color spread, headlined “Wild Kingdom,” with a photo of Gus Hebb holding Gertrude. Reporter Paul Edward Parker wrote that Hebb had spent more than a million dollars building his wildlife refuge, which he preserved while surrounding farms were being carved into housing developments. “I could’ve been a rich man,” Hebb told the reporter, “but I’ve spent all my money on this sanctuary. You have to really devote your life to something like this, accept the losses, plan to die broke.”

Only a handful of researchers had ever been inside, but now it would be open for a single day to Common Cause members for $30 each.

From phone calls and the flurry of replies that arrived each morning, it was hard to tell whether crowds were coming because this would be the first public look at Hebb’s fabled wildfowl sanctuary or because there had been a surge of converts to the cause of reform. “Bring them all in,” said Natalie Joslin. “They all become members of Common Cause.”

Fall colors neared their peak on a crystalline October Sunday when volunteers lugged cases of wine up the stairs to Gus Hebb’s interconnected treetop platforms. Caterers positioned gourmet boxed lunches on long tables. Hundreds of cars threaded their way into a fresh-mown field, where students directed them to park in tight rows. Political candidates who had not made reservations appeared, paid admission, and worked the crowd.

Gus Hebb alternated between anxiety that the hoard of people might unnerve his animals and exuberance as he welcomed more than twelve hundred visitors to his sanctuary. Since my first visit, he had rigged an elevator for any who could not manage the stairs to his treetop platform. His lift groaned like an industrial hoist but did its job.

His African crowned crane chicks and their regal parents wowed the crowd. Bird-watchers with cameras peered into cages and craned their necks. The Treetops felt solid underfoot even with a thousand people filling its platforms and walkways from railing to railing. Maples at their autumn best seemed to dance in the sun.

From a podium with brilliant color at his back, Gus Hebb welcomed the crowd. “I wanted to open this place as a way of thanking Common Cause for being up there at the State House every day, fighting for us,” he said. He urged everyone present to join the battle against corrupt government.

Alan Hassenfeld picked up on that theme, reminding people it had been barely more than ten months since we unveiled the RIght Now! Coalition with pealing church bells. “Our goal from the beginning has been to make Rhode Island what it should be — a place of hope, a place of equality, a place of freedom — rather than what it had become — a place of despair, a place of inequality and special interests, a den of corruption, almost a prison.”

Applause swelled.

Hassenfeld turned toward the future, a final seventeen days before the election when Rhode Islanders would vote on Question One. In a familiar flourish, he asked each person present to talk with others about four-year terms. “In the toy business,” he said, “it all comes down to retail sales. If each of you takes a bunch of flyers with you today, and you reach out to ten friends or family members who may be skeptical, we will win this mother of all referendums.”

Never one to take himself too seriously, Hassenfeld ended by turning a phrase of Robert Frost: “I have miles to go before I sleep. I have promises to keep, so no more will Rhode Island weep.” He winked and laughed.

The crowd laughed with him and washed the woods with warm applause.

During the election’s home stretch, David Duffy’s firm produced three television commercials for four-year terms. The first started with a cuckoo clock whose hands spun forward over the sound of an accordion playing a frumpy waltz. A door on the right side popped open, and a mechanical puppet wearing a straw hat ran out, revealing campaign signs, confetti, and bunting. An amused voiceover said, “Two-year terms force the governor to spend as much time running for office as running the state.”

Another door sprang open and a puppet circled out, sitting at a desk with American and Rhode Island flags behind him. The clock chimed, and a yellow cuckoo popped out above them, crying, “Cuckoo! Cuckoo!” While the bird swung frenetically back and forth between the campaigner and the working governor, the announcer urged viewers to vote “Yes” on Question One. “It gives the governor four years to do the job right. Two years is for the birds!”

In the second commercial, the same friendly voice announced that Question One would “give the governor four years to do the job right.” The camera zoomed in on the denim pant-legs and heavy work boots of a man hop-stepping to kick. “And here’s the kicker,” the voice-over continued, “It gives you the power to exercise this option.” A close-up showed the face of a politician turning in fright as the booted foot shot past the camera and landed hard. The ad ended with a bold sign and voice: “Vote yes on #1. Four years. Time for a Change.”

In two wacky fifteen-second spots, Duffy and his team had captured the essence of complex arguments.

The third featured a merry-go-round whirling brightly at twilight, appealing to parents’ hope for their children in Rhode Island. The announcer asked if we could again make the state a joy for our children.

Alan Hassenfeld had put up $50,000 for production, companies would pay TV stations, and Duffy would book broadcast times. I began to believe we could overcome the cynicism.

But the bitter aftertaste of corruption remained. One chilly October night, I finished speaking at the Sockanosset Cross Road Library in Cranston. As I walked toward my car, a man who had been in the audience crushed his cigarette and shook my hand. His calloused grip felt far stronger than mine. He did not offer his name. “Things happen here that you’ll never change,” he said. He told of inspecting road construction for the Department of Transportation. He glanced into the darkness and spoke warily: “This buddy of DiPrete’s used to short us on paving contracts.”

“Shorted?” I asked. “How?”

He rubbed his thumb and index finger together, as if separating bills. “Specs might call for five inches of concrete, but they’d fill the bed a little higher and pour a half inch less. The finished road would look the same but might not last as long.”

“Which contractor?” I asked.

He shook his head, refusing to name names, and lit another cigarette.

“Did you report this?”

“I told my supervisor, and he looked the other way. So I went up the chain and reported both the contractor and my supervisor. And do you know what happened?”

I shook my head.

“Exactly nothing. Except I got transferred off that job.”

“We have a whistleblower law,” I said.

He shrugged. “And how many guards will you give me?”

He helped organize coalitions that led in passage of dozens of ethics and open government laws and five major amendments to the Rhode Island Constitution, including the 2004 Separation of Powers Amendment.

West hosted many delegations from the U.S. State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program that came to learn about ethics and separation of powers. In 2000, he addressed a conference on government ethics laws in Tver, Russia. After retiring from Common Cause, he taught Ethics in Public Administration to graduate students at the University of Rhode Island.

Previously, West served as pastor of United Methodist churches and ran a settlement house on the Bowery in New York City. He helped with the delivery of medicines to victims of the South African-sponsored civil war in Mozambique and later assisted people displaced by Liberia’s civil war. He has been involved in developing affordable housing, day care centers, and other community services in New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

West graduated, Phi Beta Kappa, from Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y., received his masters degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York City, and published biblical research he completed at Cambridge University in England. In 2007, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Rhode Island College.

Since 1965 he has been married to Anne Grant, an Emmy Award-winning writer, a nonprofit executive, and retired United Methodist pastor. They live in Providence and have two grown sons, including cover illustrator Lars Grant-West.

This electronic version of SECRETS & SCANDALS: Reforming Rhode Island, 1986-2006 omits notes, which fill 92 pages in the printed text.