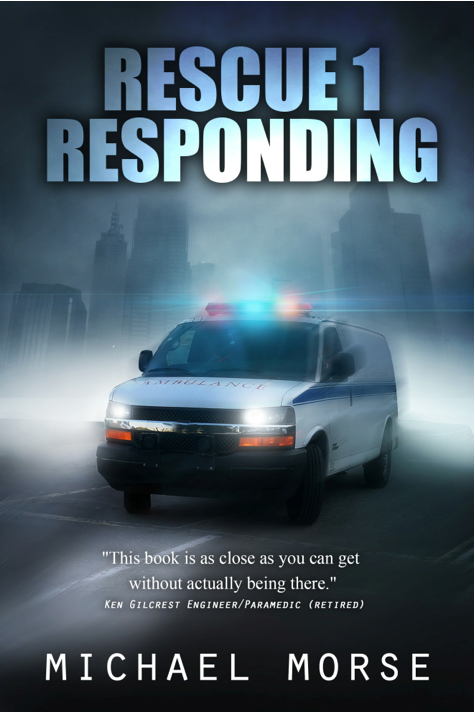

Rescue 1 Responding: Chapter 25, a Book by Michael Morse

Michael Morse, Author

Rescue 1 Responding: Chapter 25, a Book by Michael Morse

I’m glad I took the time to document what happens during a typical tour on an advanced life support rig in Rhode Island’s capitol city. Looking back, I can hardly believe I lived it. But I did, and now you can too. Many thanks to GoLocalProv.com for publishing the chapters of my books on a weekly basis from now until they are through. I hope that people come away from the experience with a better understanding of what their first responders do, who they are and how we do our best to hold it all together,

Enjoy the ride, and stay safe!

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTCaptain Michael Morse (ret.)

Providence Fire Department

The book is available at local bookstores and can be found HERE.

Chapter 25

0435 hrs. (4:35 a.m.)

“Rescue 1 and Engine 11, respond on Route 95 North, right before the Thurbers Avenue curve, for an MVA.”

“Rescue 1, responding.”

We leave the scene of the tipover and head to the wreck on the highway. There are only a couple of other cars on the road now. We ride behind Engine 11 and get onto 95 headed north to look for the accident. Sometimes the caller gives the wrong information. Sure enough, we pass an accident in the high-speed lane of 95 south. It appears to be a two-car crash.

“Rescue 1 to fire alarm, there is an accident on 95 southbound in the high speed lane right after the Thurbers Avenue curve. We’ll keep you advised if there is anything on 95 North.

“Roger, Rescue 1. Engine 11 receive?”

“Engine 11, received the message. There’s nothing ahead of us, we’re turning around and heading south.”

We follow Engine 11 as they take the next off ramp, then onto the next on ramp and head back to the accident scene. The damage to the vehicles didn’t look too serious as we passed in the northbound lanes, but you never know what to expect until you get up close. Engine 11 pulls behind the wreck to provide protection and we pull in front.

The first vehicle appears empty and undamaged. The other one has major drivers side and front end damage. Three people are in the car. I approach on the passenger side and look into the passenger compartment. Two young women are in the rear seat helping the driver; both have blood up to their elbows. The driver is a semi-conscious man who is around the same age as the girls. The side window is smashed, air bags have deployed and there is deformity to the steering wheel. One of the girls is holding a blood soaked rag against the left side of the man’s head.

“We’re going to get you out of here,” I say to the people involved as I look into the passenger side window. I know the driver needs help but I don’t know about the other two.

“Are you two okay?” I ask.

“We’re fine, but he’s lost a lot of blood. We were behind him when his car went out of control. He spun around, then hit the Jersey barrier.”

“Thanks, but what about you two?” I want to know if an additional rescue will be needed.

“We weren’t involved, we just stopped to help,” says the girl holding onto the guy’s head. I look at them and see concern on their pretty, blood and tear streaked faces.

“Do you know him?” I ask.

“No, but he needed help. We’re nursing students at Rhode Island College.”

This is just what I need about now. All week I’ve been helping people. Some have desperately needed it, others haven’t. The driver of the demolished car needed help and two people were good enough to give it. He was lucky. The best most of us do is call 911 from our cell phones and drive away, letting somebody else handle the bloody mess. What these girls did may not be the smartest or safest thing to do, but it is the most courageous. My faith in humanity is restored.

“I didn’t think anybody cared,” I say.

Mike and the crew from Engine 11 have the stretcher and backboard ready. Mike nudges me out of the way and puts a trauma dressing on the man’s head then wraps it with a roll of cling wrap. The blood soaks the dressings and immediately starts dripping down his face.

“I think he has an arterial bleed,” says Mike.

“Let’s get him out of here.”

I get out of the way and let the firefighters do their thing. Rick and Cindy from Engine 11 have the man extricated, collared and in the rescue in about a minute. His head still bleeds profusely. I give a bottle of peroxide, some sterile water and a few towels to the nursing students. It’s the best we can do. I hope they never lose the humanity they have just shown. Years of taking care of other people takes its toll, but some people are able to hold onto their compassion.

“Blood pressure 98/60, pulse 120,” says Mike. I get an oxygen mask ready and Cindy starts an IV.

“Do you need a driver?” asks Joe, from Engine 11.

“As soon as we get the IV started.” I say.

Rick gets in the drivers seat; Cindy and Mike stay in the back with me.

“All set, head to Rhode Island,” I say to Rick after Cindy establishes IV access. The truck moves, slowly at first, then picks up speed. The patient is saying he’s sorry over and over.

“What is your name?” I ask.

“Patrick. I’m sorry,” he answers.

“Do you remember what happened?”

“I’m sorry. I was driving and I lost control. I’m sorry, I might have been going too fast.”

“What is your date of birth?” I ask, while simultaneously transcribing the answers onto the State report - no easy task in the back of a rescue speeding down route 95.

“I’m sorry. Twelve, twenty, eighty,” he answers.

“Do you have any medical problems?”

“I’m sorry, what do you mean?”

“Asthma, diabetes, cancer, anything like that.” I say.

“No, but I have ADD.”

“Do you take any medications?”

“Adderol. I’m sorry.”

“You don’t have to be sorry. You had an accident, they happen all the time.”

“Yeah, but I’ve been drinking.”

“Well, nobody but you got hurt, maybe the State Police will give you a break.” I say.

“They have to. I’m in the criminal law program at Roger Williams. I want to be a cop. I’ve ruined everything now.”

“Maybe not, like I said you might catch a break.”

“I’m sorry. Can I call my mom? She just got a divorce. She doesn’t need to worry when I don’t come home.”

“We’ll call from the hospital. Try to relax, things will work out.”

I hope things work out for him. One small mistake can ruin a person’s life. Instead of a future with the police department, this poor kid might be working at a department store. I have a tendency to look at drunk drivers like they are the biggest assholes on the face of the earth. I conveniently forget my own dubious drunk driving exploits. I am lucky I was never caught. The self-righteous bullshit I sometimes throw at the drunks I pick up is just that; bullshit. Very easily I could be in their shoes, and I am not alone. Thankfully, I smartened up before I made a costly mistake. With the help of Bill W. and millions of other recovering alcoholics, I managed to put my life back together, one day at a time.

The rescue backs into the bay at Rhode Island Hospital. What a surprise, it’s almost five in the morning and there are three Providence rescues and four from other towns there with us. The back doors open and Rick starts to pull the stretcher out. I’ve slowed the IV to a drip, barely enough the keep the vein open. Too much IV fluid is contraindicated in head injuries. We wheel Patrick through the doors, past the waiting rescue crews and their patients and to the triage desk. Melanie takes a look at the patient. I give her a brief description of what happened and she decides to put him into a trauma room because of the arterial bleed.

“Can you call my mother?” he asks again.

“What’s the number?” I ask. He tells me and I write it on the report.

Back in the rescue, I pick the cell phone up and call the kid's mom. She answers on the first ring. After a few tense moments, I convince her that Patrick is alive and well.

I know how it feels to wait and worry for missing children. My two have always made it home, sometimes later than they were supposed to, but they always made it. I cannot imagine the grief that comes from losing a child. The most heart-wrenching image from my career to this point is that of a mother and father walking down trauma alley toward their dying son. He fell from a seven-story building onto a concrete driveway. He was a college kid sneaking onto the roof of his dormitory for a smoke after a stressful exam week. It was something he and his friends did all the time. This time though, he slipped on the icy shingles, falling eighty feet. His friend watched him go over the edge and frantically called 911 from his cell phone. I found a crumbled mess at the foot of the building. We did what we could. The boy’s name was John. He was conscious while we rushed him to the trauma room at Rhode Island Hospital. He tried to communicate with us, but his ruined body wouldn’t allow it. He grabbed me with his broken bones and looked at me through eyes that had been dislodged from their sockets as we rode to the hospital. We were supposed to be his rescuers, but we knew, and I think he did too that he didn’t have a chance. That ride was the longest five minutes of my life.

He was alive when we got him to the trauma room. His parents were notified and began their forty-five minute journey to their son’s side. I was sitting on the floor in the corridor of trauma alley, finishing my report when they arrived. The look of hope mingled with horror and fear was etched on their faces as they made the long walk to the end of the hall. His mother clung to her husband as they walked; he held her up and carried her. I am thankful that I wasn’t in the room when they saw the mangled body of their son. He died the next day, his parents by his side.

Light has entered the world; darkness begins its morning retreat. The birds that have adopted the awning above the rescue bay announce the start of a new day with their joyous chirping. Sunrise is still hours away, but a new day begins to form. All I want to do is go to bed. One look at Mike in the driver’s seat tells me that he feels the same. Patrick will be fine. Unfortunately, not everybody is as fortunate.